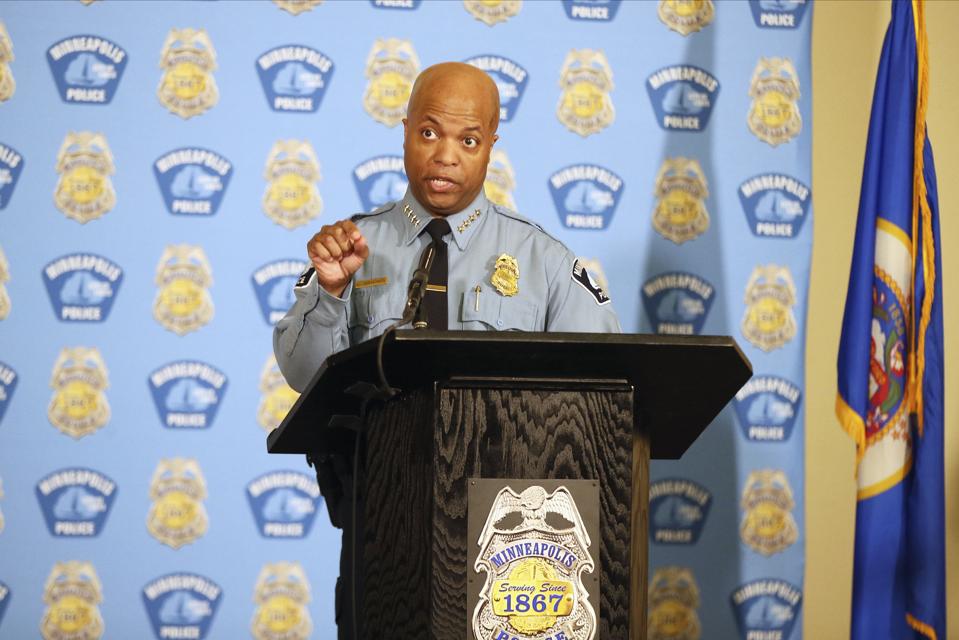

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo addresses the media, Wednesday, June 10, 2020 in … [+]

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Reported at CNN today:

“Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin could receive more than $1 million in pension benefits during his retirement years even if he is convicted of killing George Floyd.

“Chauvin has been the subject of national fury since last month, when footage emerged of him kneeling on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes as Floyd begged him to stop. He was quickly fired from the department where he had worked since 2001, and amid national protests, was eventually charged with second-degree murder. Three other officers involved with the incident were also fired and face felony charges.

“But Chauvin still stands to benefit from a pension partially funded by taxpayers. While a number of state laws allow for the forfeiture of pensions for those employees convicted of felony crimes related to their work, this is not the case in Minnesota.”

The implication here is that this is outrageous. But it’s not. It’s entirely reasonable.

Pension benefits, after all, are a form of compensation. No differently than 401(k) and similar retirement savings accounts, they are earned during the workers’ career, even though they’re not paid out until retirement. What’s more, in the public sector, workers make their own contributions in addition to their employers’ contributions. In Minnesota, participants in the Police and Fire Fund of the Public Employees Retirement Association contribute 11.8% of pay, and employers contribute 17.7% (and are on the hook, collectively, for deficits). Why so much? These employees are not a part of Social Security, and are pretty generous even for Police/Fire pensions, with an accrual rate of 3% of pay, and a fixed COLA of 1% per year. (In case you’re wondering, the plan was 89% funded as of July 1, 2019, so these contribution rates are a fairly reasonable representation of the costs of the plan.)

Quite apart from the legislation on the matter, if these sums of money had been paid into a retirement savings account, I imagine that we’d all have a reasonably easy time accepting that this was money that Chauvin possessed.

What’s more, consider the alternative in which the state would wholly seized his pension and, 25 years from now, he would return from prison with no financial resources at all. (Again, recall, he will not be eligible for Social Security.) Derek Chauvin may be evil incarnate, but this is not the right outcome, generally-speaking, either. And, what’s more, Chauvin’s wife (or soon-to-be-ex-wife) will likewise be eligible for a share of his retirement benefits — it’s hard to see justice served by taking away benefits which she is recognized to have a right to as well.

Now, to be sure, it is popular to take away pensions, and, in a 2012 compilation, fully half of states did so, though in some cases only for “public officials” or elective office-holders. And since those pensions aren’t protected by federal law in the way that private sector pensions, legally there aren’t the same sorts of roadblocks.

What’s more, states which rescind pensions have a rationale for this. Andrew Guevara, writing at ALEC in 2012, explained,

“Pensions may be considered a part of a public employee’s compensation, but contingent only on the conclusion of loyal and devoted service. When an official cheats the system, they no longer deserve these benefits. The Illinois Supreme Court summarized this contract in its 1978 ruling declaring the state pension’s board to revoke former Gov. Otto Kerner’s pension after several federal convictions. Justice Robert Underwood wrote that the public deserves the ‘right to conscientious service from those in governmental service,’ defending the necessity for pension forfeiture.”

I’ll be honest — for a state that protects its employees’ pensions so zealously that not even future accruals may be reduced, this seems a bit of a stretch to find that, all along, they are only owed if the service was “loyal and devoted.” But, at the same time, pensions for top executives work differently than for the rank-and-file in the private sector as well, at least in principle.

But there’s another element to the story: pensions can be seized as a form of restitution. This is true even of private-sector pensions, and even though those pensions are generally fairly tightly protected against other forms of garnishment. In particular, in 2006, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Victim’s Restitution Act of 1996 superseded the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (see the Pension Rights Center summary and the ruling itself); in 2015, another court drew the same conclusion in a different case.

Will Chauvin owe restitution when this is all said and done — to the Floyd family or to the state for his incarceration costs (which he would owe, if he were in Michigan)? We’ll see, as the coming chain of events play out.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!