getty

Will the HEROES Act form the basis of an eventual stimulus-spending deal, if indeed there is one? Current reporting focuses on the amount of spending on such particulars as stimulus checks, unemployment boosts, and the like, while ignoring the endless list of additional provisions, from ballot harvesting to a T-band auction repeal, to yes, a new variation on a multiemployer public pension bailout (see my summary from earlier this week), and it is by no means clear whether these are the subject of the backroom negotiations, or conceded by one side or the other already.

But, again, the existing legislation contains $676 billion in money to be sent to state and local governments: $257 billion for state, territory, and tribal governments, as well as $179 billion for local governments, $208 billion for states specifically for education spending, and $32 billion for mass transit entities.

Recall that Illinois had, quite some time ago now, gotten the ball rolling on bailout requests all the way back in April with its $41.6 billion request. And, to be fair, the HEROES Act, in terms of money directed specifically to states, allocates a fair bit less than this. But let’s look at how it’s doled out:

In Rep. LaHood’s “good-governance strings-attached” version of state and local relief, most money was allocated in proportion to a state or locality’s population, with small flat per-state sums. That’s not at all the case with the HEROES Act.

In the HEROES Act, money for states is allocated based on the proportion of unemployed workers (p. 45). The only contingency is that that money be used to cover direct covid costs or economic impacts or to make up for lost revenues. Given that the HEROES Act is itself full of endless appropriations which repeat the magic words “offset the costs of impacts due to the coronavirus pandemic or public health measures related to the coronavirus pandemic,” to justify all manner spending from child abuse prevention to the Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (p. 38), this hardly seems like a restriction with teeth.

In addition, of the local government money, $63 billion would be allocated to cities over 50,000 in population (that is, “metropolitan cities” per the HUD definition), based on a formula which is partially proportionate to population but primarily based on poverty rates. $27 billion would be given over to states to allocate by population, and $90 billion would be paid to counties in proportion to their population.

The majority of the education-specific spending would be allocated based on state proportions of school- and college-aged children/young adults, with a substantial minority allocated based on proportions of children in poverty (p. 150); it’s intended to be used to “maintain or restore State and local fiscal support” for education, with very few restrictions, but one key one: states must not make budget cuts in their own education spending, nor may they reduce compensation or any other provisions of a collective bargaining contract, nor may local school districts reduce payroll, at least “to the greatest extent practicable” (p. 158). What’s more, they may not use HEROES funds to provide funding to any private elementary or secondary schools, except when it’s mandated by a disabled student’s IEP.

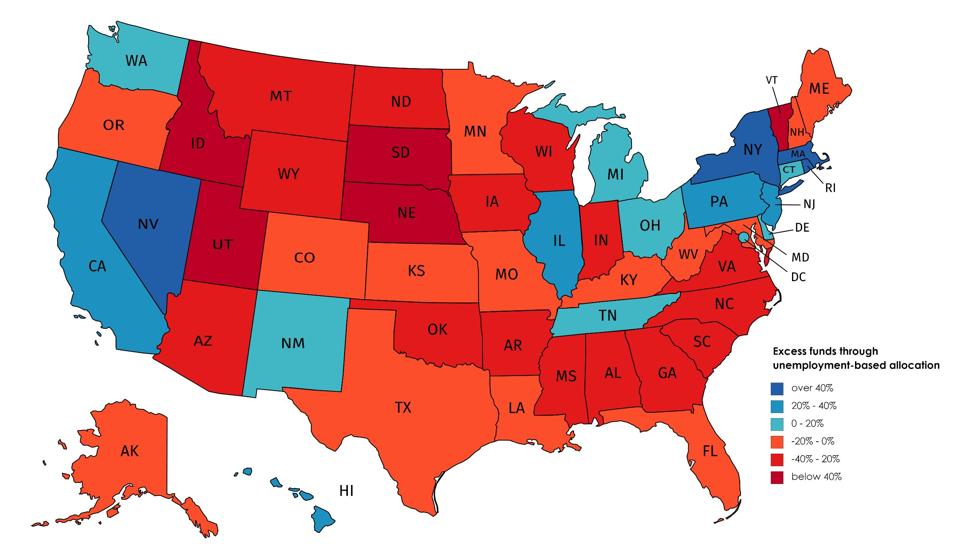

Now, the metrics for the local government and school spending money are not easy to replicate, but unemployment numbers are easy to find, and it’s a simple matter of math to compare the winners and losers of using an unemployment-based allocation instead of a population-proportionate allocation. Here’s a map, based on August unemployment data:

Winners and losers in an unemployment-based fund allocation

own work

(No, I don’t know why Tennessee’s so different than its neighbors.)

Red states lose out if a by-unemployment fund allocation is adopted; blue states win, with darker shades indicating the extremes. For what it’s worth, if this map were replicated solely based on statewide poverty rates, the numbers would look different: Mississippi would get 60% more funds than a pure population basis, and Louisiana 55% more — but that’s based on 2019 data, the most recent generally available, and, of course, the actual poverty-basis allocation in the HEROES Act is for urban areas, whereas poverty in the deep south is more likely to be rural.

(For a complete table, scroll down to the bottom.)

Now, to a certain extent, it seems fair to say that states with the most unemployment suffer the most, and are most in need of aid. New York’s unemployment rate is 12.5%; Nevada’s is 13.2%. But this metric is still faulty.

In the first place, it rewards those states which were most aggressive about their lockdowns. California, in particular, has maintained tight restrictions, continuing to forbid indoor worship services, and holding counties to a standard of less than 7 cases per 100,000 per week in order to reach the “minimal” restriction, in which restrictions nonetheless continue, for instance, restricting restaurant, fitness center, church, and other venues’ capacity to 50%. (There is no status in the state’s current plan in which restrictions are removed.) In addition, the state has implemented new “equity” requirements, in which, to move to a less-restrictive level, a county must meet certain equity requirements, by requiring that the poorest quartile of a county must meet the required metrics rather than only the county as a whole.

Is this reasonable? One might say that, in a democracy, this is merely a matter of officials elected by the people of California making decisions they judge best. But should they be be “rewarded” by Congress with extra funds?

What’s more, of course, August 2020 is but one snapshot in time, and does not measure how states have been impacted over the course of the pandemic up until now, nor what paths they might follow in the future; for instance, various of the Great Plains states are now being impacted that had not been affected much by the first months of the pandemic.

In addition, there are significant differences in the changes in the labor force, due to discouraged workers, workers leaving the state, or for other reasons. While the civilian labor force, in total, fell by 1.6% from last to this August, the rates by states ranged from a drop of 7.4% in Iowa and 7.2% in Massachusetts to an increase of 2.0% in Texas and 2.6% in Delaware. (See the below table.)

Finally, do these numbers — again, $676 billion in total — make sense relative to states’ actual fiscal losses?

Brookings recently projected state and local tax revenue losses of $155 billion in 2020, $167 billion in 2021, and $145 billion in 2022, which means that, even being as charitable as possible, the proposed HEROES spending is over $200 billion more than even this three year revenue loss. To be sure, states would (or, at any rate, Illinois would) use their money not only to cover budget holes but also to boost spending on rental assistance, for example. But for how many years after the immediate crisis is over, can one credibly insist that the federal government continue to hand over “pandemic” funds to states? And at the same time, can states truly be relied on to spend money that goes much further than their immediate needs, in order to “save” for future budget holes?

There is no simple answer to any of this.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!

Winners and losers for an unemployment-based allocation of federal funds

own work