On Thursday night’s Democratic debate stage, at least one candidate might mention the idea of supplying you with free cash simply for being a U.S. citizen.

So what gives?

The concept of universal basic income — generally a set amount of money that all people receive monthly, no strings attached — is not a new one. Yet it’s an approach that has gained some traction in the U.S. as a way to combat persistent poverty, a widening wealth gap and the ongoing automation of jobs.

Zapp2Photo | Getty Images

While not the only Democratic presidential candidate to support giving cash to at least some Americans, Andrew Yang, who was one of 10 to qualify for his party’s third debate ahead of next year’s primaries, has hung his campaign hat on what he’s dubbed the “Freedom Dividend” — a version of universal basic income.

“The idea of creating an income floor for people is really important,” said Natalie Foster, co-chair of the Economic Security Project, which is researching the effect on free cash on targeted households.

“It’s an old idea, but it’s gaining momentum now for a lot of reasons, and I’m not surprised someone is campaigning for president on it,” Foster said.

The idea of creating an income floor for people is really important.

Natalie Foster

co-chair of the Economic Security Project

A former tech entrepreneur, Yang says automation is going to continue displacing jobs and that giving every person age 18 to 64 a monthly $1,000 would ease the impact on the U.S. workforce. His plan would give current welfare and social program recipients a choice between their benefits — i.e., food stamps, housing vouchers — and the cash.

To help pay for his plan, he says he would impose a so-called value-added tax on companies for the goods and services they produce. Some estimates have pegged the cost of his plan at more than $3 trillion a year, although he has argued that the new business tax (and some other changes to the tax code), coupled with increased economic activity and reduced spending on other government services, would pay for it.

While Yang is considered a long shot for the nomination — polls show him getting roughly 2% to 5% of the vote — and a dramatic shift in federal policy would be an uphill battle, variations of his plan are already being tested in the U.S. through small-scale programs that target low-income adults.

For instance, in February, 125 residents of Stockton, California, received the first of 18 guaranteed monthly income payments of $500 through a city-led guaranteed income initiative. One of the program’s partners is the Economic Security Project, which also is supporting a similar test program in Jackson, Mississippi.

In the Stockton project, participants already are reporting that they are spending more time with children, sleeping better and feeling less stressed overall.

Those results echo some early findings from a two-year study in Finland. In that research, preliminary results showed that while participants had improved well-being — fewer problems related to health, stress and ability to concentrate — there was no difference in employment.

The lack of an uptick in workforce participation is something that critics of universal basic income point to as problematic.

“It would make things worse because it would encourage people to work less,” said Robert Rector, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. “Universal basic income displaces work instead of complementing it.”

Labor participation rates already have been falling over the last 20 years in all age groups except among people age 55 and older, according to government data.

The drop has been more pointed among men: 69.1% in 2018, down nearly six percentage points from 74.9% in 1998. That compares with women’s 2018 participation rate of 57.1%, a slide of under three percentage points from 59.8% in 1998.

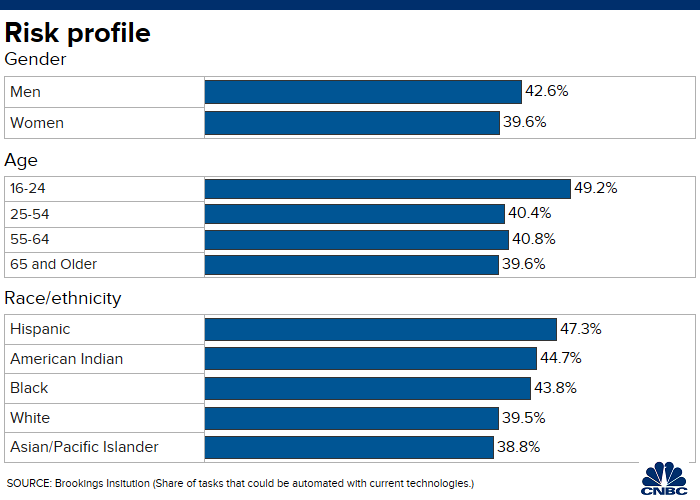

About one-quarter of jobs in the U.S. are at “high risk” of automation, according to a report from the Brookings Institution.

It would make things worse because it would encourage people to work less.

Robert Rector

senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation

Foster, at the Economic Security Project, said her group supports a different approach to creating guaranteed income. While it wouldn’t encompass all earners, it would involve expanding the existing “earned income tax credit” to a larger share of taxpayers.

That credit is generally available to working taxpayers with children, as long as they meet income limits and other requirements. Some low earners with no children also are eligible. Because it’s refundable — meaning it could result in a refund at tax time even if your tax bill is zero — it’s considered valuable to working parents with low or modest incomes.

“Why not just build on that?” Foster said. She said that it could even include a monthly cash payment so people wouldn’t have to wait until tax time to get at least some of it.

Sen. Kamala Harris, a California Democrat also on the debate stage Thursday night, is sponsoring a bill in Congress that would give families up to $6,000 a year in a refundable tax credit, which would be able to be accessed monthly — i.e., another form of basic income for families earning up to $100,000.

Rector, of the Heritage Foundation, has a different idea for that earned income tax credit that would give people more cash each month: He’d take the amount it costs the government — $63 billion in 2018, according to the IRS — and instead supplement lower-income workers’ paychecks. In other words, the government would provide a dollar amount that gets tacked onto the hourly wage, up to a certain number of hours per year, for lower-earners.

More from Personal finance:

Here’s how much other people really tip

Your Social Security checks could get bigger next year.

Average FICO score hits all-time high

“You’d be supplementing income from working, not displacing it,” Rector said. “My alternative would be like universal basic income, but would attach a work requirement. That’s good for the recipient and fair to taxpayers.”

Whether Americans support the concept of universal basic income might depend on how it’s framed: In a 2017 Gallup poll that asked if they support guaranteed income for workers who lose their jobs because of advances in artificial intelligence, respondents were split: 48% for it and 52% against it.

A more recent NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll, however, asked respondents about support for universal income of $1,000 per month for each American 18 or older: 26% said it was a good idea, 66% said it was a bad idea, and 8% said they were unsure.

Foster said there are good reasons for the U.S. to consider a guaranteed basic income for those who most need it.

“The nature of work is changing, people are feeling much more financially precarious, entrenched poverty isn’t budging and the wealth continues to grow at the top,” she said. “Having a guaranteed income floor is a big solution for a big problem.”

CNBC’s John Schoen contributed to this report.