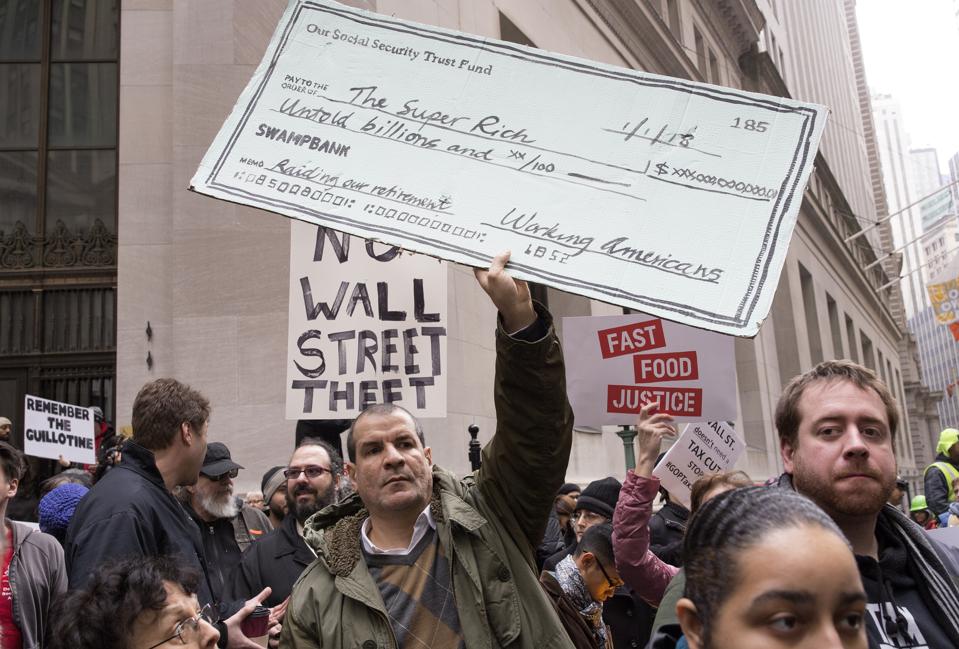

NEW YORK, NY – DECEMBER 19: Protestors demonstrate against the 2017 tax bill about to be passed by a … [+]

With all the problems the country faces—real at-home messes like the brutal costs of higher education, housing, climate change, crumbling infrastructure, and so much more—extra money should be welcome.

After all, through our elected representatives, we had the massive tax cut for corporations and the wealthy, seemingly never-ending wars and military engagements around the globe, and a foundation of constant deficit spending that might as well have us declare the era of modern monetary theory, where you’re supposed to be able to spend as much as you want so long as inflation doesn’t kick in. Which it hasn’t. Yet.

And it makes sense that extra money is good news. That’s what J.W. Mason, assistant professor of economics at John Jay College, CUNY and Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, smartly noticed in the Congressional Budget Office’s latest 10-year budget and economic forecast:

“In their most recent 10-year budget and economic forecast, the CBO made a big change, reducing their long-run forecast of the interest rate on government bonds by almost a full percentage point, from 3.7 to 2.9.”

Well, by 0.6 percentage points, but let’s not quibble overly. That’s a significant drop in rate, and as anyone who has ever had a credit card, car loan, mortgage, or payday loan knows, lower interest means less overall spending. Over the next decade, that means a reduction in debt payments of $2.2 trillion. Or, as he wrote:

“Under the assumptions that the CBO was using at the start of this year, the debt ratio under existing policy would reach 120 percent by 2040. Using the new interest rate assumption, it reaches only 106 percent. With one change of assumptions, a third of the long-run rise in the federal debt just disappeared.”

Now for the bad news. We still have massive spending and the tax cut driving a ballooning deficit. As the Treasury noted today in the final monthly statement for the fiscal year that ended in September, the deficit was $984 billion. That compares to $779 billion for fiscal year 2018. That’s a 26.3% jump. At this rate, we use up that $2.2 trillion in probably two years.

Mason sees this as a non-problem, saying that “anyone arguing that federal debt is a climate-change-level threat to humanity needs to update their talking points” because the debt won’t grow as large as previously expected. Instead of close to 150% of GDP by 2050, it’s less than 120%.

However, there are many assumptions built into the statement—and Mason’s conclusion (although I wish I felt the same ease he did in the suggestion) that the money could be diverted to healthcare or climate remediation. They include the expectation that interest rates and inflation won’t rise in the next 30 years, investors will never become nervous about U.S. borrowing, and a debt-to-GDP ratio of 120% is somehow safe.

But we don’t know any of this. Yes, interest rates are at a level so low that you’d almost have to dig a ditch for them to sidle downward even more. And there are negative interest rates in Europe and Japan that help continue to make U.S. sovereign debt seem like the single safest investment one could make. But is that guaranteed to continue? Absolutely not. It might, but what if it isn’t?

As for that 120% range, the chief strategist at a major global investment manager was discussing the subject of national debt with me not long ago. He said that it took a 180% level of GDP debt for Greece’s finances to finally explode. But who knows what the number will be for another country in the future?

Economics are as much, if not more, a matter of individual and mass psychology as they are of mathematics. As Mason notes, there seems to be no correlation between a high debt-to-GDP ratio and rising interest rates. But that’s for right now. Economists have been scratching their heads over why, for example, unemployment can continue to drop without a significant increase in wage growth. The Federal Reserve is pumping money into trying to keep so-called repo overnight lending rates low after the rates had jumped unexpectedly by a factor of five in September. What is it that we actually know?

The “laws” of economics are nothing more than a model of what has been observed in the past. If expectations, built on those previous observations, are out of sync with today’s reality, why assume that tomorrow there will be another deviation?

It would be wonderful if we could put all the money necessary to fix the major problems in the country. But what if things flip upside down? It will be the economically disadvantaged who will suffer most as politicians look for quick solutions to that can kicked down the road so often that it has picked up dirt and pebbles and clods of grass to become the size of a boulder. Those “leaders” will turn to Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and domestic spending even as we will likely be in another war demanding more blood and transfer of trillions into the hands of defense contractors that turn around and contribute to campaigns to ensure continued patronage.

We need to look now at questions of debt, adequate tax amounts (which will mean more to be paid by those who have seen massive reductions), and a cutback in types and levels of spending for destruction that should never happen so casually as they do in this country.