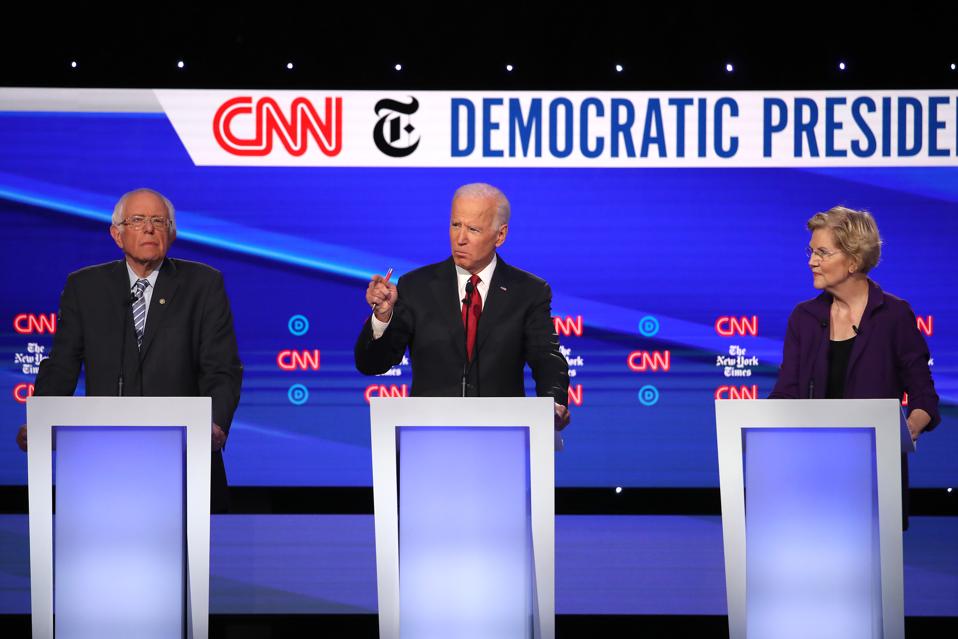

WESTERVILLE, OHIO – OCTOBER 15: Former Vice President Joe Biden speaks as Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) look on during the Democratic Presidential Debate at Otterbein University on October 15, 2019.(Photo by Win

Getty Images

In a new report, my Urban Institute colleagues have estimated that a full-blown Medicare for All plan would increase federal government healthcare spending by a net of $32 trillion over the next decade.

If you love the idea of a universal single-payer government health insurance program, you have to explain how you would finance it. And that means you must, in some way, confront a complex series of trade-offs—many inextricably tied up in the tax code.

In Tuesday night’s Democratic presidential debate, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) was asked repeatedly how she’d pay for Medicare for All. And each time she dodged the question.

A bank shot

Shifting from today’s mix of private and public health insurance to a public-only program is a complicated policy bank shot: The nearly half of Americans who have employer-sponsored health insurance would lose that coverage but get government insurance instead. They would no longer have to pay premiums and most out-of-pocket medical costs such as deductibles and co-pays, and may even get a pay raise. But they’d also have to pay taxes on those new wages that they don’t pay on their health benefits. And the nation must somehow finance the $32 trillion ten-year cost of that universal public insurance.

Bernie Sanders, who “wrote the damn bill,” does admit this, though he underestimates the price. Warren, so far, has dodged the financing issue.

Hot buttons

To understand why this is such a hot button question, think about what health care costs in the US, how we pay for it, and how the tax code subsidizes health insurance.

In 2017, the US spent about $3.5 trillion on health care, according to government estimates. Private health insurance (already heavily subsidized by government) covered about one-third, or $1.2 trillion, and Americans paid about 10 percent out of pocket. Public programs like Medicare and Medicaid paid the rest.

About 153 million Americans get their health insurance through their employer. On average, workers pay 18 percent of the premium for single coverage and 30 percent for family coverage, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Their employers pay the rest—roughly 70 percent of premiums for a family plan.

In actual dollars, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that a typical plan in 2019 costs $20,576. Employers pay an average of $14,561 and workers pay $6,015.

The employer share is tax free to workers. If your employer pays $15,000 annually for your family plan, you pay no income or payroll tax on that benefit. But if you are in the 32 percent tax bracket and your firm gives you $15,000 in cash, you’d owe roughly $5,000 in extra federal income tax (plus additional payroll tax and possibly state income tax).

The trade-offs

That’s something like what would happen with Medicare for All. Employers would no longer offer tax-free health benefits. They’d adjust compensation so workers would get back at least some the value of that foregone insurance in higher wages, (economists disagree on how much). And workers would be taxed on their raise.

At the same time, government would pay for nearly all medical costs in the US. But with what money?

Instead of a specific financing plan, Sanders has suggested six pages of possible options. Most are new taxes on wealthy households and large corporations but two are what he describes as “income-based premiums.” Sanders estimates that one, a 7.5 percent payroll tax on employers, would raise about $3.9 trillion over 10 years. The other, a 4 percent income tax surcharge on households, would raise $3.5 trillion over a decade.

Sanders says the employer tax would cost firms about $3,750 per employee, only about one-quarter of what they pay for typical health insurance premiums today. He says the extra income tax would cost a family of four that makes $50,000 and takes the standard deduction about $844 annually, only about 14 percent of their share of workplace health insurance. Plus, this household would owe no deductibles or copayments as they do with typical employer-sponsored coverage.

Where will the money come from?

Of course, as incomes rise, the net savings shrink. Based on Sanders’s own online calculator, the benefit would disappear entirely for joint filers with $6,000 in annual medical expenses and about $175,000 in income.

But there is a problem: If the Urban estimates are correct, the two tax increases combined would cover only about one-quarter of the cost of a full-blown Medicare for All plan. Where will the rest come from?

The federal government already is running a $1 trillion annual deficit that is expected to grow even under current law. And both Sanders and Warren have ambitious new spending plans for education, housing, environmental protection, and jobs on top of their health initiative. The story of how they’d pay for universal public health insurance is not a simple one. But they need to tell it.