President Ronald Reagan signs the Social Security Act Amendment with Vice President George Bush (far r), Senator Bob Dole (2nd from l), and Congressmen Tip O’Neill (4th from r) and Daniel Moynihan (5th from r) on hand as witnesses. (Photo by © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Historical | Corbis Historical | Getty Images

The year was 1983 when something unusual happened: Republicans and Democrats compromised and passed landmark legislation to reform Social Security.

The deal came from an unlikely pairing: then-President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, and Tip O’Neill, a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts and Speaker of the House.

Together, with majority Senate leader Howard Baker, R-Tenn., they set up a bipartisan commission to evaluate Social Security. On April 20, 1983, Reagan signed amendments to the program that ushered in changes in financing, coverage and benefit rules.

Recently, Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, unveiled a new proposal for Social Security that advocates setting up bipartisan committees to look at repairing the program’s balance sheet, as well as those of the nation’s Medicare and highway programs.

The proposal has some concerned that history will repeat itself and usher in one change: raising the full retirement age again.

What is full retirement age?

Full retirement is defined as the age at which eligible workers can receive 100% of their retirement benefits based on their work record.

A separate number, 62, is the age when workers are first eligible to collect retirement benefits. But by claiming early, they will receive reduced monthly checks for life.

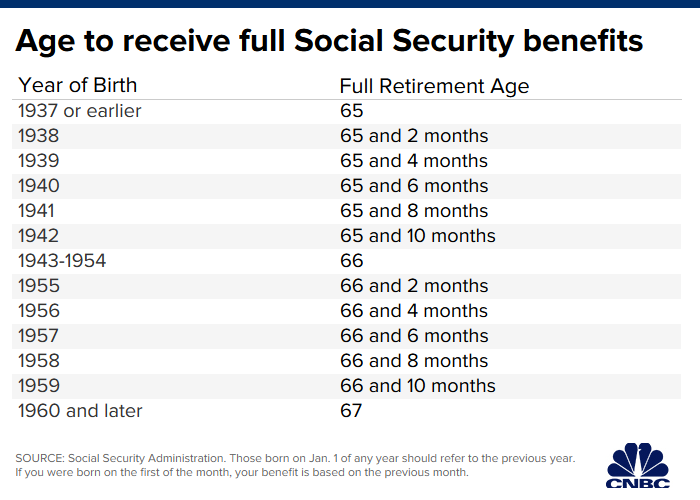

Full retirement age was traditionally age 65. However, that changed with the 1983 legislation signed by Reagan, which gradually pushed the full retirement age up to 67, depending on an individual’s birth year.

Additionally, individuals who delay claiming benefits past their full retirement age stand to receive up to 8% more per year up to age 70.

As it currently stands, only 80% of promised benefits will be payable by 2035 if nothing is done to shore up Social Security.

To fix that, politicians face the difficult choice of either raising taxes or reducing benefits.

“When Congress is considering, ‘How are we going to make Social Security balance in the end?’ it’s probably going to be a combination of revenue increases and some benefit cuts,” said Richard Johnson, director of the program on retirement policy at the Urban Institute, a non-profit research organization.

Why raising the retirement age is controversial

Some Republicans, including Romney, have discussed raising the retirement age as part of Social Security reform. The bipartisan Simpson-Bowles plan, more formally known as the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, included a proposal to raise the Social Security retirement age to 69 by 2075, among other changes, in order to help cut the national debt.

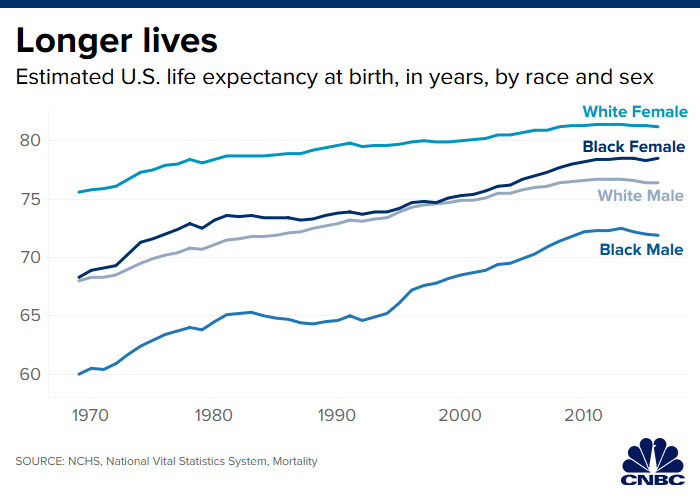

“When Social Security first started, the average life expectancy was 17 years lower than it is today,” said Rachel Greszler, research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. “And yet, the retirement age has only increased by two years.”

While Greszler said it could make sense to raise the retirement age, not everyone agrees that such a shift would work.

Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, said she doubts that increasing the retirement age would make sense the way it did in 1983.

That’s because a lot of people are going into retirement unprepared. Take our current 401(k) program, for example. It hasn’t produced a lot of retirement savings, she said. A typical 60-year-old had less than $100,000 saved in their 401(k) in 2016, according to the Center for Retirement Research. Meanwhile, half of workers don’t have access to a workplace retirement plan at all, Munnell noted.

“When you look at the retirement system as a whole, there’s not a lot of other sources of money for people other than Social Security,” Munnell said.

Another concern is that while life expectancy is going up, it isn’t increasing equally across the population. For some lower income groups, life expectancy has been stagnant for the past 20 years, Johnson said.

How it could trigger other changes

Many individuals can’t hold out to claim Social Security at their full retirement age, either because of no employment or poor health, and consequently claim as early as they can at age 62.

However, if the full retirement age is raised and the earliest age to claim stays the same, individuals will receive even less in benefits at 62, Johnson said.

Some advocate bumping the initial retirement age to 64 or 65 from 62 to eliminate that problem. That doesn’t address what would happen to people who cannot work at age 63 or 64 until they become eligible for benefits.

More from Your Money Your Future:

Mitt Romney pushes new plan to fix Social Security

This bill could extend Social Security’s solvency

Social Security benefits to get a 1.6% boost in 2020

“There are a lot of people who are really counting on Social Security as an important lifeline,” Johnson said. “If we remove that lifeline, what happens to those people? That’s kind of the policy dilemma.”

On the other hand, lawmakers could increase incentives to wait to claim to 75 from 70, Johnson said.

Research has shown that increasing the full retirement age does prompt individuals to work a little longer.

“People seem to take this full retirement age as kind of a signal as to when the appropriate time is to retire,” Johnson said.

That can be good for workers because those extra years in the work force allow them to save more and let their benefits increase. It’s also good for society, as those workers continue to pay taxes and increase workforce productivity, Johnson said.