Employees of the General Electric (GE) company arrive for an inter-union general meeting in Belfort, eastern France, on October 7, 2019. – The management of General Electric (GE) in Belfort said on October 3, to be “ready” to maintain a maximum of

AFP via Getty Images

Last week, General Electric announced the impending freeze of its pension plans to new accrual, for salaried workers and executives. And, as much as we’re accustomed to the stories of woefully-underfunded public pensions and multi-employer pensions, it’s worth taking a look at the situation at GE, and asking the question, why were GE’s plans so underfunded that they felt it necessary to take this step?

(And, yes, part of the answer is simply, “everyone’s doing it” and per the statistics in that prior article it is somewhat of a natural next step to freeze pensions to new accrual some years after closing them to new entrants, but there is more to the story.)

In the case of multi-employer pensions, the story is familiar: pension funding levels drop during bear markets, funding legislation requires that they make up the deficits within a given number of years, they apply for hardship exemptions because of the burdens that a requirement to bring the plan up to full funding would produce for participating employers, sooner or later the chickens come home to roost.

But GE?

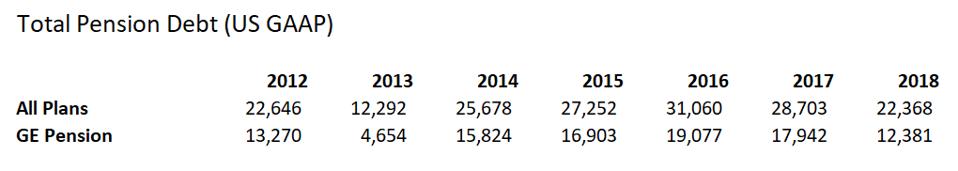

On its balance sheet, at year-end 2018, its plans were 76% funded (see p. 127 ff). That doesn’t look too bad, compared to the levels of plans like Illinois’, Chicago’s, or Central States. But the company’s pension plans are so massive in size that this underfunding amounted to, in dollar terms, $22 billion in debt, out of a total pension liability of $92 billion. That’s 20% greater than its market capitalization of $77 billion.

And let’s break that liability down:

$68.5 billion comes from what the company calls its “principal pension plans” – the GE Pension Plan for salaried and hourly workers and the supplemental pension plan for executives.

Of this, $6.1 billion comes from the supplemental plan, which is unfunded. The remaining $62.4 is the main pension plan, which was 80% funded at year-end 2018, which translates into a $12.4 billion underfunding.

The remainder of the $92 billion comes from “other pension plans”; to what extent these are non-US pension plans isn’t clear from GE’s financial reporting but it’s no doubt a significant part of the total (the plans’ weighted average interest rate is much lower than for the “principal plans” which suggests these are plans in Europe, where rates are much lower).

And $12 billion and $22 billion, for the GE Pension Plan, and for all pension plans, respectively, is a lot of money, but that debt level has declined since its peak at year-end 2016.

GE US GAAP funded status, from 10-K reporting at GE.com

own work

So why was the main pension plan underfunded to the tune of $12.4 billion? After all, the federal government has fairly tight regulations to ensure that plans are appropriately funded. Why wouldn’t these regulations have achieved this goal?

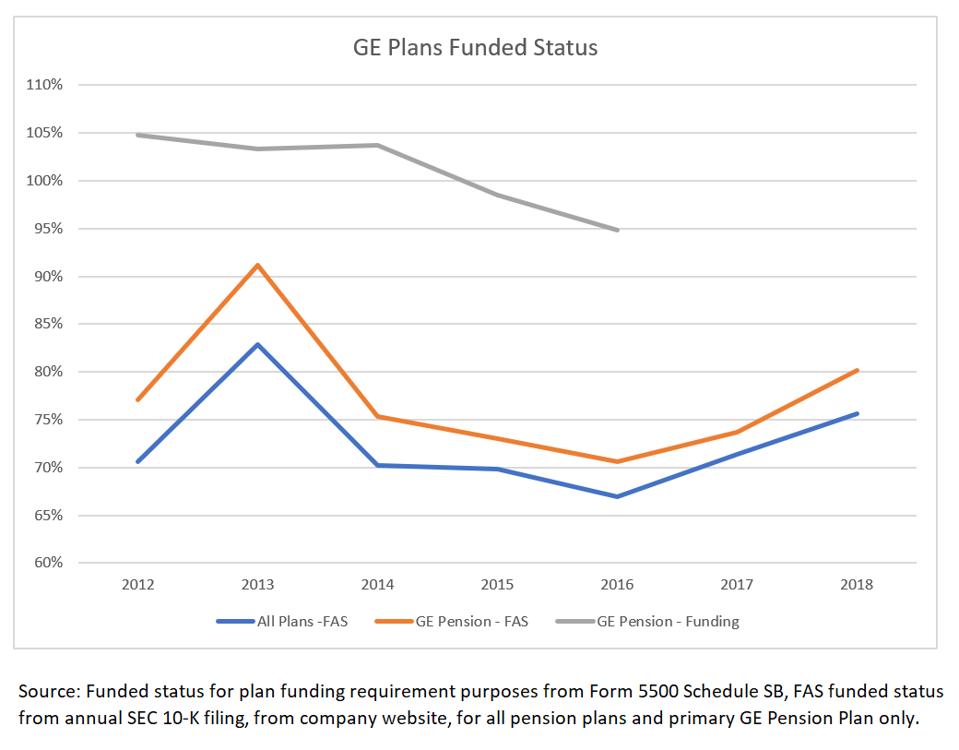

Turns out, as far as the government is concerned, the plan is 95% funded – or, rather, as of the most recent data available from the IRS Form 5500 Schedule SB funding requirements filings, at the beginning of 2017, when on an accounting basis the plan was 71% funded, its funded status, according to the federal government’s funding requirements, was 95%, and the plan was making contributions fully in compliance with those funding requirements.

GE funded status history, per accounting and funding requirements

own work

In fact, the 10-K’s statement on contribution policy says (p. 131),

“Our policy for funding the GE Pension Plan is to contribute amounts sufficient to meet minimum funding requirements under employee benefit and tax laws. We may decide to contribute additional amounts beyond this level. We made contributions of $6,000 million and $1,717 million to the GE Pension Plan in 2018 and 2017, respectively. Our 2018 contributions satisfied our minimum ERISA funding requirement of $1,500 million and the remaining $4,500 million was a voluntary contribution to the plan. We currently expect this voluntary contribution will be sufficient to satisfy our minimum ERISA funding requirement for 2019 and 2020.”

Why is there such a sharp discrepancy between the US GAAP/accounting and the statutory funding-requirement funded status? In the first place, the statutory funding requirements as dictated by the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) are based on the “accrued benefit liabilities,” that is, benefit accruals based on employees’ pay at the time of the valuation; US GAAP financial reporting uses the Projected Benefit Obligation, which calculates liabilities based on plan participants’ pay at retirement. In the second place, when interest rates began dropping drastically, Congress passed “funding relief” in the form of MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act; yes, this was tacked onto a transportation bill) in 2012, which set minimum interest rates and smoothed those interest rates; at a point when the US GAAP rate was 4.11%, the funding interest rate was 5.92%. (Readers who observe me on my soapbox regularly will know that the higher the interest rate, the lower the liabilities, and the better the funded status.) Third, plans report their assets for funding purposes on a smoothed basis, which boosts funded status in bad years and reduces it in good years. And, finally, plans file their Schedule B reporting forms after the close of the plan year and include additional contributions made in fulfillment of that year’s funding requirements, rather than the simple snapshot-in-time asset valuation used for financial reporting.

All of which leads to the larger question: should the government have had tighter funding regulations?

As it happens, in some respects, the PPA was a substantial tightening of funding requirements when it was implemented in 2006: it required plans to remedy funding shortfalls within 7 years (compared to as many as 30 years for benefit increases previously) and it required the use of a corporate bond rate rather than an expected investment return basis for liability valuations. It also provided significant room for employers to fund their plans more conservatively if they chose, although, as the American Academy of Actuaries points out in its analysis of the law, there are some shortcomings and it lacks incentives to more fully fund its pensions, particularly to a level based on its accounting liabilities, in part because, if interest rates rise again and plans become overfunded, companies can’t get that money back. And, of course, beyond this, employers are limited in their ability to fund executive pensions, and overseas pensions are a whole ‘nother story.

But the PPA is focused on ensuring that plans are well-funded on the “accrued” level that’s the amount participants are guaranteed by law. Whether companies exceed this for the sake of their financial results is a business decision like any other.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!