by Tax Notes State Commentary Editor Doug Sheppard

In one of the most famous scenes from The Blues Brothers, Sister Mary Stigmata doles out rapid-fire corporal punishment with a ruler on Jake and Elwood Blues, then breaks it on Elwood’s head before Jake crashes down an adjacent flight of stairs in the ensuing chaos.

“Get out! And don’t come back until you’ve redeemed yourselves,” a mortified Sister Mary says, before closing the door.

Chicago native Marilyn Wethekam has never confronted anyone quite as outspoken as John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd in her 43 years in state and local tax, nor did her alma mater — Regina Dominican High School — ever face the threat of closure over a tax bill like Sister Mary’s Roman Catholic orphanage.

But thanks to the example set by Regina Dominican nuns as wise as Sister Mary, she was ready for the turbulence she encountered as a female state and local tax pioneer.

“It didn’t come out of the blue,” Wethekam said. “To be honest, I was well-prepared for it. I went to an all-girls Catholic high school in Wilmette that basically taught all of us that we could do whatever we wanted to do; we could be whatever we wanted to be. And because we had a group of nuns who politely taught us, you didn’t have to take anything from anyone. We were better prepared for it than some people are today.”

And while Wethekam hasn’t broken a ruler on any male SALT colleague’s head, she’s channeled some of her nun mentors’ strength into the workaday world, particularly when confronted with sexist — or at least inappropriate — treatment.

“You took a lot, and you had to figure out how to deal with it,” Wethekam said. “And one of the ways to deal with it was to show you wouldn’t take it, right? But rather than get square in someone’s face, there were other ways to deal with it; there were more subtle ways to deal with it where they got the point.”

Those more subtle ways, according to Wethekam, include sarcasm and returning a snide comment for every one received until “you get that kind of ‘woah,’ deer-in-the-headlights, step-back look. And you only have to do that a couple of times, and they realize that ‘OK, I’m done trying to intimidate,’ so now you’re part of the group.”

But as anyone who’s worked with her will tell you, Wethekam was always part of the group — and not just because she had a few zingers up her sleeve in less enlightened times.

Backing Into SALT

While attending Loyola University Chicago for undergraduate studies from 1969 to 1973, Wethekam “always wanted to go to law school.”

And after earning her bachelor’s degree in political science, she went to Illinois Institute of Technology for her law degree, which she achieved in 1977.

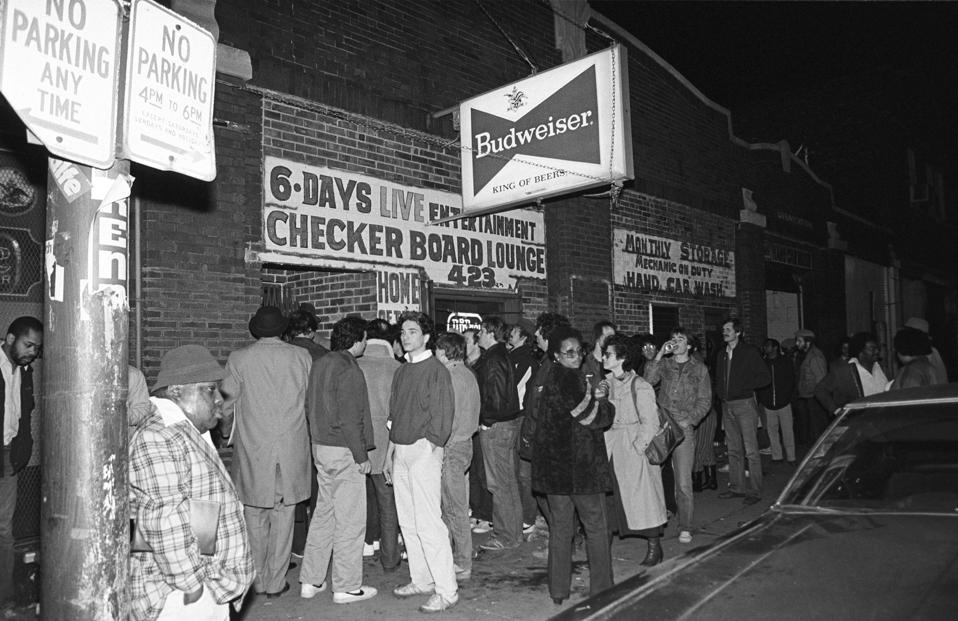

Finding a career path was less clear-cut, as Wethekam recalled. As Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, and the other elders of Chicago’s legendary blues scene played local clubs like the Checkerboard Lounge, Wethekam was singing her own brand of blues — that of a woman trying to break into the male-dominated legal field.

Scene from Muddy Water’s wake at the Checkerboard Lounge, Chicago, Illinois, May 3, 1983. (Photo by … [+]

Getty Images

“I literally backed into SALT,” Wethekam said. “When I got out of law school in 1977, the market for lawyers — particularly female lawyers — wasn’t great in Chicago. There were 10 women in my law school class, and almost all — and I actually tried this, too — went into some sort of public service; they either were state’s attorneys, public defenders, or something along those lines.

“I tried to get into the public defender’s office, and did interview with it, and did some pro bono work with them in juvenile court with the hopes that I would catch on,” she added. “And I didn’t.”

In 1978, however, a Montgomery Ward classified ad in the Chicago Tribune caught her eye: “State tax counsel, no experience needed.”

“I thought, ‘Well, OK. I fit the latter part.’ I wasn’t exactly sure what the job entailed,” Wethekam said.

Having been in the job market for approximately six months, Wethekam wasn’t about to let the opportunity slip away when she landed an interview. Not even the somewhat awkward setting could stop her: The job interview took place at Montgomery Ward’s corporate offices on Chicago Avenue, which were near the river in Cabrini-Green, “one of the more infamous housing projects in Chicago,” as Wethekam recalled. “I interviewed for the job, and I got it.”

Fortunately for Wethekam, the apparent resistance to women in the legal field in late-’70s Chicago didn’t extend to Montgomery Ward, where she met two of her mentors, Jerome “Jerry” Lutz, the company’s sales tax director, and Jim Devitt, its state and local tax director (who later went on to Kraft Foods).

“Both of them took me under their wing and gave me advice on how to deal with all of this, and really taught me what I needed to know,” Wethekam said. “So my SALT knowledge evolved, and both of them were very supportive of me being involved in organizations, letting me learn, and teaching me SALT.”

Devitt, who chaired the Committee (now Council) On State Taxation from 1978 to 1980 and was a board member from 1971 to 1987, was pivotal in getting Wethekam involved in COST: “He was very supportive of me getting involved in that, and a lot of what I learned, I learned going to COST meetings.”

And speaking of COST chairs, Jim Buresh — chair from 1984 to 1988 and a board member from 1981 to 1993 — “was probably equally as much of a mentor and equally as instrumental in getting my career to where it is today,” according to Wethekam. Among other things, Buresh — with whom Wethekam never actually worked in his career path at Sears, Arthur Andersen LLP, and Deloitte — uttered a line about women in the workplace that has stuck with her to this day.

“I don’t want my [two] daughters treated that way, so why would I treat you that way?” Buresh told Wethekam early on.

“I’ve used that line when things have gone south, so to speak — that ‘Look, you have daughters. Really, do you want them treated that way? So come on, behave yourself,’” Wethekam said.

The Rise of Women in SALT

Like the state and local tax field itself, women in SALT had yet to reach their full potential in the early ’80s. Wethekam learned just how far women had to go when she attended her first COST sales tax meeting in 1982.

“Let’s just say that when I showed up at the first COST meeting, there were maybe three females in the room — and one of them could have been Carol [Calkins],” Wethekam recalled. “Now today, if you went to a COST meeting, more than 50 percent of the room would be female — probably close to 70 [percent]. But in those days, we stood out. Everybody knew we were there — for a lot of reasons.”

But for women to make that progress, SALT would also have to make inroads. At the dawn of the 1980s, progress was slow.

“In the early ’80s, state tax was just an offshoot of federal — and it was kind of an afterthought,” Wethekam said. “People would look at you and say, ‘You really want to do state and local tax? You don’t want to do federal or international tax?’ Federal tax was the gold standard. SALT was kind of the poor stepchild, so to speak.”

However, California’s imposition of worldwide unitary combined reporting led to a dialog between President Ronald Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and, ultimately, to Reagan’s formation of the Worldwide Unitary Taxation Working Group in 1983. By 1984, the group had issued a report advising against worldwide combination, which proved to be a catalyst for growth of the SALT practice.

“Suddenly SALT received more notoriety because of this working group that was put in place at the federal level,” Wethekam said. “And as you moved to the late ’80s, there were a number of cases that had been moving through the courts, and I think major corporations realized that while federal tax was important, what they were paying in state taxes in some cases — depending on what type of tax you were talking about — could exceed what you were paying at the federal level. As a result of that, I think people realized that there were some opportunities on the planning side, but certainly it was an area that needed to be looked at.”

Accounting firms also took notice of the importance, building SALT practices from the ground up.

“The accounting firms were starting to put together these state and local tax groups, and as a result of that hiring more people and realizing that there was an expansion needed here because there were opportunities out there — either from a planning opportunity standpoint or just a growth standpoint,” Wethekam said. “So once you saw the Big Eight growing, the growth of SALT went along with it.

“And in corporate America, you could see where SALT and federal started to be linked. And if you put a team together because you were going to do an acquisition or you’re going to do a disposition or something like that, you would start to see teams with actual state and local tax people on them. So it wasn’t an afterthought after the deal was done; there wasn’t an ‘oops.’”

Like the booming expansion of the western United States in the 19th century, the SALT train was already rolling full speed down the track — and nothing stood in the way of its growth. By the ’90s, it was almost like the California gold rush.

“In the ’90s, it exploded when law firms realized that they couldn’t just do state and local tax with their federal guys, accounting firms were growing their staffs, and corporate America realized that this was important,” Wethekam said. “On the corporate America side, a lot of it has to do with COST becoming very active.”

The rise of COST in the early ’90s was coupled with very active state organizations like the Multistate Tax Commission and the Federation of Tax Administrators, according to Wethekam, creating “this kind of mix of friendly adversarial concepts going back and forth about how this was going to evolve. So I think that helped a bit, too. We saw some growth there.”

Increased activity on all fronts led to more employment opportunities, which in turn saw women making considerable inroads in the field.

“It was obvious from the late ’80s through all of the ’90s that there was a growth in women becoming involved in SALT,” Wethekam said. “There were certainly more women going to law school and graduating from law school, and realizing that this was a great area to get involved in. From an accounting standpoint, I think you saw more women go to business school than you had in the ’70s or the early ’80s. You had many more women graduating from business school, many more women graduating with accounting degrees, and this was a field that was exploding — so it was just natural to get involved in it.”

As a result, women went from being a tiny minority in SALT to equal partners in many respects — if not the majority in some scenarios, as Wethekam noted earlier in the change in the composition of COST meetings.

“When you got to the mid-’90s to the early 2000s, I think you saw a huge growth of women becoming involved in this — and taking supervisory roles at the accounting firms and in corporations, where directors of state tax were now female rather than male,” she said. “In the early 2000s, you saw a number of female VPs of taxes — whereas you wouldn’t have seen that in the ’70s or ’80s.”

How has all this struck Wethekam, a veteran of the era of male dominance?

“It’s great that it’s grown,” she responded. “It is really nice not to be the only woman in the room — not to be the token, so to speak.”

Striking Tax Oil

During her tenure at Montgomery Ward, Wethekam earned her LLM in taxation from John Marshall Law School in 1983: “I think it gave me a good background in federal tax theory. I have to admit, though: I’m not sure I have ever really used my LLM in the SALT world. But it did give me some background in federal tax theory. Once you take a deep dive into the consolidated return regulations, you’ll understand that. Montgomery Ward did not suggest I do that; I did that one on my own.”

On the other hand, Wethekam’s undergraduate degree has served her well in unexpected ways.

“My undergraduate degree is in political science, and I took a number of constitutional law classes as part of that, even some graduate classes as an undergraduate — and I always liked that,” she said. “And when I went to law school, constitutional law and those type of classes were really what I excelled in; I didn’t do overly well in property. And so I realized that SALT, as I was starting to get into it, really had a constitutional bent. It had some challenges to it, because there’s obviously 50 states with 50 different statutes, and you had to learn them all.”

With that background, plus 10 years at Montgomery Ward under her belt, Wethekam sought a new challenge when she took another tax counsel position at Mobil Oil Corp. — which owned Montgomery Ward — in September 1988. “I joined Mobil as part of a transfer, which actually in retrospect was a very good move since Ward’s went bankrupt twice,” she said.

The new job briefly took her to New York (until December 1988), followed by nearly seven years in Dallas, where she joined Mobil’s three other state tax counsels at its state and local tax group headquarters.

The sign for Mobil gas is seen at a Mobil gas station in Los Angeles, October 26th 2019. (Photo by … [+]

Hulton Archive

“Both Montgomery Ward and Mobil gave me great opportunities not only to get involved in state tax, but also — particularly Mobil — had some really interesting transactions, and they were very big on putting a team together,” Wethekam recalled.

“So you had international representation, federal representation, and SALT representation — and I had the privilege of being on a number of those teams. So it was a great learning opportunity to some really detailed, complicated transactions. But they also were very supportive of getting out in the community and being involved in state taxes at a different level. Both companies were instrumental in boosting my career.”

COST’s First Female Chair

Perhaps the biggest boost occurred in 1992 when, after eight years on its board, Wethekam became COST’s first female chair.

The appointment was as much a trial by fire as it was recognition, bringing what Wethekam described with a new twist on an old metaphor: “If that was a glass ceiling I broke, I got cut on the way through occasionally.”

To put it another way, anyone expecting June Cleaver instead got Koko Taylor, the graceful silver-throated queen of Chicago blues. One of Taylor’s signature songs is “Fire,” and Wethekam had plenty of that.

“It didn’t always go smoothly,” Wethekam said. “There were individuals who I think wanted to test the first female COST chair — and maybe I was the wrong one to test. There were individuals who wanted to exert control because they thought they had the authority to do so, so there were some rocky moments with explaining that they didn’t. So I did get a few shards of glass on the way through regarding that.”

One of Wethekam’s main tests as COST chair started with developments that preceded her tenure. Before her appointment, Paul Frankel of W.R. Grace and Buresh (then at Sears) had instituted COST’s audit sessions, in which members meet to share information about state auditing practices.

“At that point, there was no other place to get that information in the entire country, and it was just a membership organization,” COST Executive Director Doug Lindholm said.

Lindholm continued: “Around that time, Paul Frankel left to go to Morrison & Foerster LLP, but W.R. Grace said, ‘We would like to continue having Paul as our representative on COST.’ So Jim and Paul would run the audit sessions, and Paul continued to do so as the representative for W.R. Grace while working for Morrison & Foerster.”

When Buresh left Sears for private practice at Arthur Andersen, he expected the same treatment — but the new chair objected, a stance that was not necessarily popular.

“Marilyn, to her everlasting credit — and I thank her for this every day that I’m at COST — said, ‘Look, we are much more effective if we keep practitioners at arm’s length and we just share information among the membership. We remain an organization of companies without practitioners.’ Keep practitioners as partners and obviously work with them, but preserve the membership as company-only,” Lindholm recalled.

Wethekam’s actions, according to Lindholm, were pivotal in the history of COST.

“That has had a huge impact on our ability to share information and to be a membership organization,” Lindholm said. “If you think back, Marilyn had to push back against some of the leading lights of COST at the time — all adult white men. The character and the courage it took to do what she did was truly breathtaking — and again, I give her all the credit for preserving COST for what it is today.

“I think we’re much more effective because of the way that we treat the relationships with practitioners differently from members,” Lindholm added. “Not to say that we don’t appreciate practitioners, because we certainly do, but we appreciate working with them as partners and not as members.”

For her part, Wethekam looked back on the controversy with a touch of humor. “Some of them were not quite ready to see a female chair,” she said. “So they had to be dealt with. And in all honesty, I dealt with them politely, but there were some moments when you kind of wanted to go into a room, close the door, and just scream.”

Buresh, it should be noted, was actually pivotal in Wethekam’s ascension. “Jim was very good for someone I never worked for or with, because we never were in the same organization,” she said. “Jim really took me under his wing and said, ‘I’ll help you in your career,’ and he was instrumental in getting me up the COST ladder, and ultimately to be the chair of COST.”

Wethekam served as COST’s chair until 1994 and remained on its board until September 1995, when she left Mobil for private practice as a partner at Horwood Marcus & Berk Chtd. (recently rebranded as HMB Legal Counsel) and — if you’re keeping score — remained true to her convictions by shifting her relationship to an associate who continues to do presentations at COST meetings.

“The SALT world itself had pretty much exploded,” Wethekam said of her move into private practice in 1995. “You now had law firms being involved in it, states had become much more sophisticated in their audits, the issues had become more sophisticated, and you could just see it evolving into as complicated of a practice as federal tax or international tax.”

By that time, Wethekam had earned the respect of her colleagues. Retired practitioner and fellow pioneer Carol Calkins, who’s known Wethekam since the 1980s, described her as “one of the most outstanding state and local professionals practicing today.”

“Marilyn is sort of like Cher,” Calkins said. “She is so well known in SALT circles that when you say Marilyn, everyone knows immediately who that is.”

“I’ve always had a tremendous amount of respect for Marilyn,” added Lindholm. “I really enjoy working with her in whatever capacity — as a practitioner and when she was a COST member. She’s truly a pioneer and deserves all the recognition that she gets.”

Mentoring

As one would expect from someone with over 40 years in SALT, Wethekam has acquired her share of wisdom that she’s given back to younger practitioners — both men and women.

Lawyers and businessmen join hands in business After signing the legal consultancy contract

getty

“Certainly I have been a sounding board for people who are younger than I am, who have grown up — and tried to grow up — in this field as to what’s the best approach and how to go about it,” Wethekam said.

“So I have taken on that role a little bit in the firm on the tax side, not in some of the other areas of the firm. I am more than willing to help people grow in this field and make sure they succeed, because I think that’s the key. Sometimes a little advice helps you succeed. People certainly took me under their wing, so there’s no reason for not paying it forward.”

What are her main pieces of advice for those starting in SALT?

“A couple of things,” Wethekam responded. “I think one, to be substantively sound: Pick your topic and make sure that you understand it. It can be overwhelming, but just take it in small bites and make sure you understand what the topic is and what surrounds it. Two, when you don’t understand something, don’t be afraid to ask; no one will hold that against you. So if you don’t understand something and you want to talk through it, ask. Everybody is more than willing to teach. And last but not least, don’t take yourself so seriously, because something’s going to happen, and you’re going to just have to roll with it sometimes.”

In the less serious moments of her leisure time, Wethekam enjoys golf, skiing, paddle tennis, and pickleball — not to mention watching her beloved Chicago Bears and Chicago Cubs. SALT made all those moments sweeter.

“SALT has been very good to me and I’ve enjoyed doing it,” Wethekam said. “It’s a very interesting field, because you have 50 states involved, and no two are alike. It’s been a good 40 years of a career.”