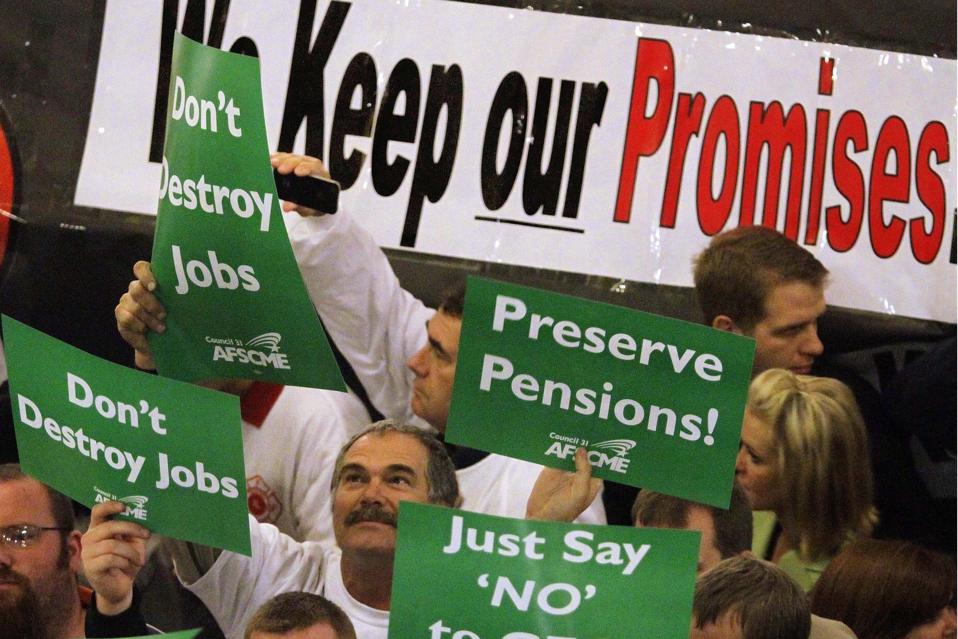

In this Oct. 26, 2011 photo, police officers, teachers, caregivers and other rank-and-file public … [+]

“Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.”

That’s Article XIII, Section 5, of the Illinois constitution approved by 57% of the 37% of voters who voted in a December 1970 special election.

Did voters know that they were binding future generations to a promise that legislatures could increase pension benefits at any point — which they did, repeatedly — but could never reduce them, not even with respect to pensions not yet accrued, regardless of how expensive those pensions would become?

Via an online database, I took a look at the reporting at the time in the Chicago Tribune. Various articles highlighted some of the key issues being debated in Springfield: “home rule” of cities, amount and types of taxes the state and cities would be empowered to raise, whether judges would be appointed or elected, whether the legislature should be selected via cumulative voting or single-person districts, among others. The new constitution eliminated the prior prohibition on gambling, which meant at the time that bingo games would be legalized, and included firearms-ownership rights. Delegates considered banning capital punishment, but this proposal was defeated. (See, among others, “Here’s What Illinois Con-Con Has Done,” by John Elmer, April 20, 1970; “Fate of Con-Con Largely in Hands of Daley, Observers Indicate,” John Elmer, Sept. 7, 1970; “Foes Forming To Destroy Con-Con Plans,” John Elmer, June 7, 1970.)

But the pension protection clause?

Nothing.

The only newspaper item in which this appears is a document titled, “Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention Address to the People,” published on behalf of the delegates on Nov. 22, 1970, briefly explaining the document and the voting process, and asking for voter approval. This document says:

“The provisions of state and local governmental pension and retirement systems shall not have their benefits reduced,”

which, of course, fails to meaningfully inform the public that the document on which they are voting guarantees not only benefits accrued-to-date (as they might reasonably expect in comparison to private-sector pensions) but also benefits not yet earned, that is, for future service credits.

And, again, this vote on the constitution offered Illinoisians the opportunity to decide on four separate items themselves rather than being subject to the decisions of the convention delegates. With respect to judicial election or appointment, single-member or cumulative-voting districts, the death penalty, and the voting age, voters were not constrained to an all-or-nothing, up-or-down vote. Not so with pension guarantees.

Now, perhaps one might say that this means that it was wholly noncontroversial that future accruals as well as past benefits should be protected. After all, the constitution delegates were chosen on a nonpartisan basis, at least on paper — in actual practice delegates were supported by the party machines of the party in power in one area or another, that is, Chicago vs. downstate, as they were the ones with the mechanisms to ensure voter turnout, rather than some idealized scene of local community leaders coming together. (See “State Constitutional Convention, ‘69: Big Issues at Stake for the Voters,” John Elmer, Sept. 22, 1969.) And in Illinois, home of “The Combine” and bipartisan corruption, it’s hardly necessary to have one-party dominance, for politicians to make decisions that are all about preserving their power without regard to the well-being of the people of the state.

What’s more, the writers of the state’s constitution included a means of amending the document via the collection of petition signatures — but they limited this only to amendments pertaining to the constitution’s Article IV, which has to do with the legislature: its composition, the redistricting process, the timing of its sessions, etc. An amendment to any other section of the constitution may only be accomplished through the legislature’s voting by three-fifth’s majority to place an amendment on the ballot, and then passage by three-fifth’s of those voting in the subsequent election.

All of which makes the statements of the Illinois Supreme Court, in its 2015 decision overturning the 2013 pension reform law, farcical (however true, in some legal construction, they may be):

“Article XIII, section 5, is in no sense a surrender of any attribute of sovereignty. Rather, it is a statement by the people of Illinois, made in the clearest possible terms, that the authority of the legislature does not include the power to diminish or impair the benefits of membership in a public retirement system. This is a restriction the people of Illinois had every right to impose. . . .

“The people of Illinois give voice to their sovereign authority through the Illinois Constitution. It is through the Illinois Constitution that the people have decreed how their sovereign power may be exercised, by whom and under what conditions or restrictions. Where rights have been conferred and limits on governmental action have been defined by the people through the constitution, the legislature cannot enact legislation in contravention of those rights and restrictions. . . .

“Article XIII, section 5, of the Illinois Constitution (Ill. Const. 1970, art. XIII, § 5) expressly provides that the benefits of membership in a public retirement system ‘shall not be diminished or impaired.’ Through this provision, the people of Illinois yielded none of their sovereign authority. They simply withheld an important part of it from the legislature because they believed, based on historical experience, that when it came to retirement benefits for public employees, the legislature could not be trusted with more (p. 22 – 24).”

Yes, in a legal sense, the Illinois constitution is, in a grandiose sort of way, The Will of the People. But one can’t help but feel that, in writing these words, the Court was mocking the powerlessness of the people of Illinois who had no real control over any of these decisions.