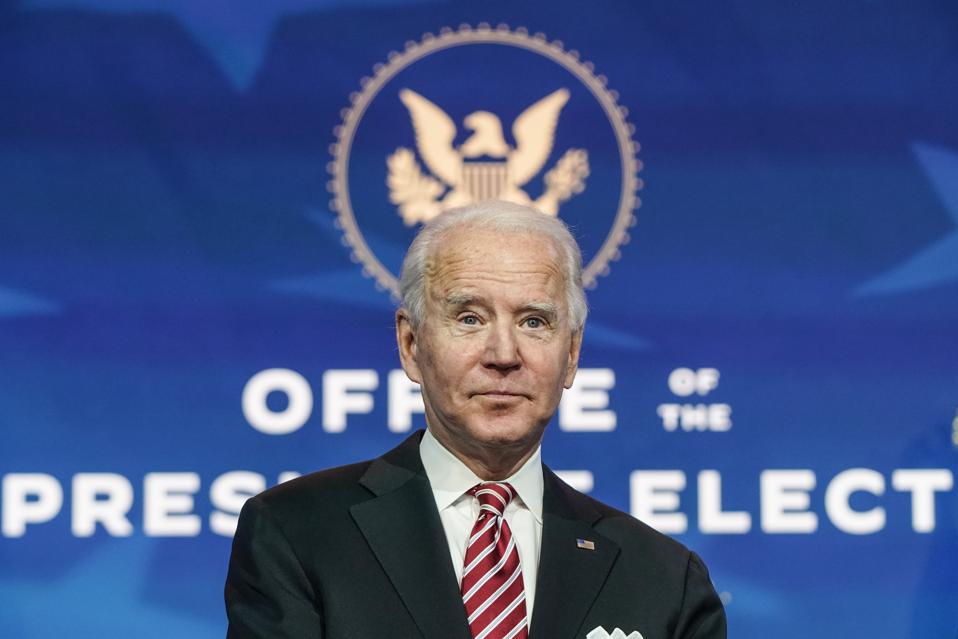

WILMINGTON, DE – DECEMBER 23: President-elect Joe Biden announces Miguel Cardona as his nominee for … [+]

Getty Images

A little over a year ago, back when Sen. Elizabeth Warren was considered a contender for the Democratic presidential nomination, I wrote about her plan for “accountable capitalism,” that is, among other things, a plan to mandate that 40% of board of director seats at American corporations with over $1 billion in revenue, be reserved for individuals elected by employees and representing their interests. I referenced an analysis by a liberal writer, Matthew Yglesias, that suggested that share prices could fall by 25% in such a case — an outcome he judged satisfactory because he believed it would penalize the rich, but in reality it would penalize all Americans who own stock indirectly as well, through 401(k)s or pension funds. In fact, fully half of all US-owned US stocks are owned within retirement funds, so this would affect vast numbers of Americans, not just the rich.

Now, Elizabeth Warren’s candidacy has come and gone, and this specific proposal was not among President-Elect Biden’s proposals, but that doesn’t mean that this has become a non-issue. Yesterday, Biden named Boston Mayor Marty Walsh as his future labor secretary, a move NPR connected to Biden’s campaign promise to be the “most pro-union president you’ve ever seen,” because of Walsh’s deep ties to unions. His promises include a federal ban on state “right-to-work” laws, the implementation of “card check” unionization, the adoption of California-style tests for independent contractors, effectively banning gig workers such as Uber

UBER

And back this past summer, Biden called for “an end to the era of shareholder capitalism,” leading George Tyler, writing at Fortune Magazine in December, to make the following call:

“The alternative to this model is stakeholder capitalism, where corporate boards pursue policies that benefit local communities and employees in addition to shareholders. Biden embraced stakeholder capitalism in a speech in July. But he was silent on the mechanism utilized by rich democracies of Northern Europe to effectuate stakeholder capitalism—a mechanism that economists call codetermination. In codetermination, management and workers cooperate in decision-making, especially through the representation of workers on boards of directors.

“Minority Leader Charles Schumer and 13 other Senate Democrats have endorsed codetermination, and rightly so: It is the only version of capitalism proven effective in improving the economics of non-college workers along with other stakeholders. Just as it has in Northern Europe, a Biden administration embrace of codetermination can transform U.S. corporate boards from predators to advocates for working-class Americans.”

MORE FOR YOU

Is he right? Turns out, just last month, a group of economists (Christine Blandhol, Magne Mogstad, Peter Nilsson, and Ola L. Vestad) published an analysis answering this very question, and their findings are, well, not what you’d expect. Yes, they find that “a worker is paid more and faces less earnings risk if she gets a job in a firm with worker representation on the corporate board.” But that’s not because worker representation actually improves employee well-being. Instead, corporations with worker representation are larger, on average, than firms overall, and are more likely to be unionized; and it is these characteristics that boost worker pay and job security, not corporate board representation.

Their conclusion: “these findings suggest that while workers may indeed benefit from being employed in firms with worker representation, they would not benefit from legislation mandating worker representation on corporate boards.”

Now, to be sure, their analysis was based on developments and comparisons in Norway, where codetermination laws were implemented in 1972 and operate on a sliding scale, with representation requirements increasing as company size increases. And their analysis doesn’t definitively determine that there were no changes to pay and job security due to this legislative change at the time when it was made in Norway or in other countries; it just makes comparisons based on the present situation.

But it does call into question the promise that codetermination is a sure thing towards achieving its supporters’ goals. And it would be deeply unfortunate if we end up with the worst of both worlds, and a drop in share values hurting our retirement funds without making workers better off at all.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!