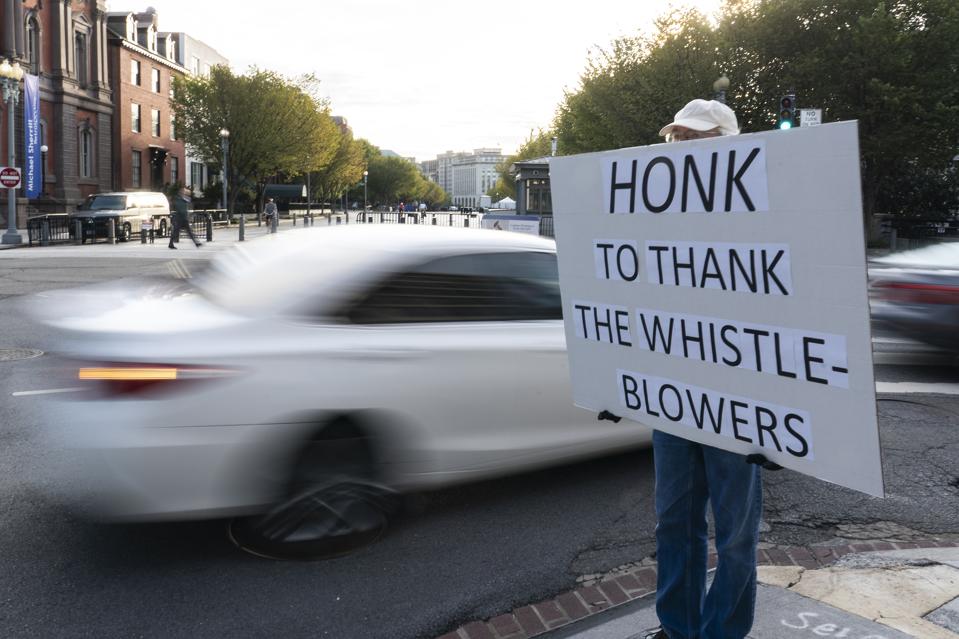

A demonstrator holds a sign reading “Honk To Thank The Whistleblowers” near the White … [+]

I often am asked by beleaguered corporate whistleblowers for advice on how to survive and prosper as a whistleblower. While the American public overwhelmingly applauds the important work of whistleblowers exposing illegalities, it is generally acknowledged that whistleblowers pay a heavy price. Indeed, last week I was profiled in a CNBC video How Corporate Whistleblowers Make Millions precisely because the producers wanted to tell the story of a successful whistleblower that wasn’t financially ruined, divorced or blackballed within his industry.

My first experience as an SEC whistleblower was in 1988 when I was—a a mere three years out of law school and still very young—Legal Counsel and Director of Compliance to one of the largest global asset managers.

I never participated in the wrongdoing and reported it immediately upon discovery. Ironically, the violations were initially brought to my attention by certain ethically inclined young and idealistic employees within the firm.

I did not look for trouble—wrongdoing—it found me.

I was initially applauded, promoted and given a raise for reporting the wrongdoing to my employer. I was told I had “saved the reputation of the firm.” Additional activity later came to light which required reporting to SEC—blowing a silent whistle. There was no reason for me to go public.

Fortunately, as a former SEC attorney-adviser in finance, I had fully investigated both the investment and legal dimensions of whistleblower matter and, perhaps equally important, I knew whom to call. There was no Office of the Whistleblower for members of the public to contact at that time. The SEC neither solicited whistleblowers nor was accustomed to hearing from them.

My first whistleblowing experience took a long time to resolve but, thankfully, ended with a record-breaking fine for the culprit.

Since I did not go public, I was not blackballed in the industry. Further, since the mutual fund industry was experiencing explosive growth at that time and I was one of a handful of lawyers in the nation with mutual fund regulatory expertise, I had multiple job offers. (One or two offers may have been withdrawn due to negative comments, as I recall.)

Most important, I had concluded by this time that the better I did my job—overseeing legal and compliance matters—the more precarious my employment would be wherever I went to work. After all, I had already, in my early 30s, conducted possibly the most extensive investigation of mutual fund wrongdoing ever—at one of the largest global asset managers.

So, I pivoted from law into the asset management and securities industry. Thanks to my former employer, I was financially well-positioned to make the transition– being young and single also helped. My legal credentials and industry experience enabled me to raise funds immediately from a large insurance company to start my first entrepreneurial venture. I have been self-employed for the past 30+ years.

A decade later (after selling my first company), I pivoted back into law and forensic investigations of asset managers. I embraced my whistleblower heritage and touted my investigative capabilities, as details of my first whistleblowing experience came to light through then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s work uncovering mutual fund scandals in the early 2000s.

I have conducted over $1 trillion in forensic investigations. I have been an SEC whistleblower hundreds of times. To my knowledge, I have successfully blown the whistle to the SEC more than anyone in history. The record is clear the SEC has heard and acted on my whistleblower complaints over the decades—significantly impacting disclosure and business practices in my field – asset management.

My advice to would-be whistleblowers:

(1) Don’t participate in wrongdoing;

(2) Report immediately to either employer or SEC, or both;

(3) Don’t go public unless absolutely necessary;

(4) Pivot to enhance career prospects;

(5) Remember you can always reclaim or publicly own your whistleblower heritage at the appropriate time—but only when it’s best for you and your loved ones.

Again, not all whistleblowers are blackballed; not all commit career suicide and most do not break the law. Indeed, in my experience most whistleblowers have profound respect for the law.