Hands Of Father Giving Jar Of Coins To Child On Wooden Table Background – Inheritance / Parent … [+]

The SECURE Act (Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement) was passed in late December and includes a variety of changes that primarily revolve around retirement plans. Let’s explore some of the most meaningful aspects of the recent legislation and how they could affect your tax and estate plan.

Starting Age for Required Minimum Distributions

One of the big benefits of a traditional IRA or a qualified plan like a 401(k) is the ability to defer paying taxes until you withdraw money from the plan. If your money remains inside an IRA or similar plan, you pay no income tax on the interest, dividends or growth of the investments inside the account. Of course, the IRS eventually wants that revenue, so there is an age by which you must start taking withdraws from your account. These withdrawals are called Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Under previous law, the age by which you had to start taking money out, and thus paying taxes on the income, was 70 and a half. Under the SECURE Act, the beginning age for RMDs is now 72.

For retirees who do not need to take IRA distributions to fund their living expenses, this is a positive change. Without the mandatory IRA withdrawals, your taxable income will likely be lower for an additional two years. Lower taxable income translates into a lower tax bill or an opportunity to strategically create income at a lower tax rates through activities such as Roth conversions.

Though the SECURE Act delayed the age for starting RMDs, it did not change the age at which you can make charitable donations from your IRA. Donations made directly from an IRA, otherwise known as Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) can still be made once you reach age 70 and a half.

Distribution Rules for Inheriting an IRA, Roth or other Qualified Plan

Beneficiaries of an IRA, Roth IRA or other qualified plan have new rules to contend with as a result of the recent legislation. The rules depend significantly on who inherits the account(s) and all center on how quickly the funds must be distributed once they are inherited.

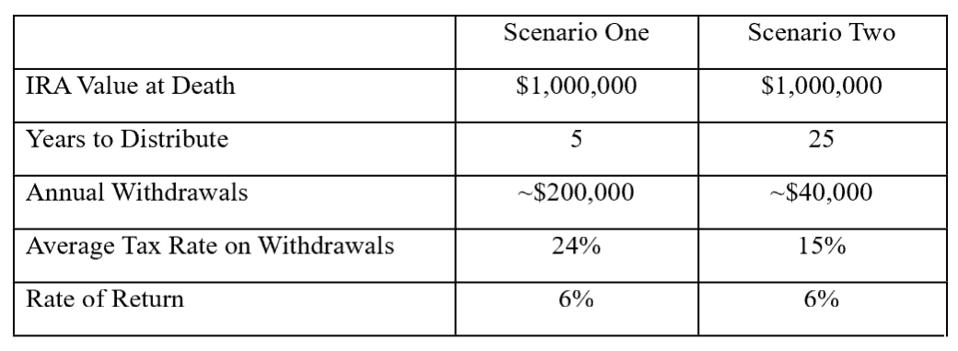

Generally, it is better to have more time over which a beneficiary can withdraw money from an inherited retirement plan. Consider this example where a beneficiary inherits a $1,000,000 IRA. In scenario one, the beneficiary must withdrawal the money within five years of inheriting it and in scenario two they can withdrawal it over 25 years.

SECURE Act

After 25 years, the beneficiary in scenario two would have approximately $750,000 more than the beneficiary in scenario one. In part, the difference is attributed to a difference in tax rates on the withdrawals. Presumably, larger withdrawals will be taxed at a higher overall rate than small ones as tax rates increase with additional income. The remaining difference is attributed to the second beneficiary’s ability to leave more money inside the IRA for a much longer period of time, allowing its growth to escape taxes on the interest, dividends and appreciation. This kind of tax-deferral is the primary appeal of investing in an IRA or similar account for retirement and it remains a significant benefit after death. Even if both beneficiaries paid the same average tax rate of 24% on their withdrawals, beneficiary two would still have about $385,000 more simply from the ability to keep money in the IRA for a longer period of time.

The SECURE Act limits the time period over which most beneficiaries can withdraw inherited retirement assets to a maximum of 10 years; whereas, the withdrawals were previously based on the beneficiary’s life expectancy. A young person who inherited retirement assets under the old laws would have been able to take gradually-increasing withdrawals over their lifetime, potentially giving them 50 years or more to distribute their inheritance from an IRA or Roth. Limiting that timeline to a maximum of 10 years will meaningfully reduce the value of their inheritance in the long run.

Though beneficiaries don’t have to take annual distributions, if they don’t empty the account by the end of the 10th year following the decedent’s death, they will face a penalty of 50% of the amount they failed to withdraw.

A select few beneficiaries will be able to continue to spread retirement distributions over their lifetime under the new laws; namely, spouses, disabled or chronically ill beneficiaries and beneficiaries who are less than 10 years younger than the decedent. Minor children may withdrawal assets over their life expectancy until they are 18 or 21 (depending on their home state), after which they will have an additional 10 years to deplete the account.

Other Changes Impacting Individuals

There are numerous other provisions in the SECURE Act, many of which pertain to employers’ and small business owners’ ability and incentive to provide retirement saving for their employees. A few other provisions that impact individuals include allowing people over age 70 and a half to make IRA contributions, distribute up to $5,000 from an IRA penalty-free for an adoption or birth of a child, use 529 college-savings plans to repay up to $10,000 of student loans per child and deduct medical expenses that exceed 7.5% of adjusted gross income.

Undoubtedly the most influential changes in the SECURE Act are the revisions for beneficiaries who inherit retirement assets. As a result, it will be important to review your tax plan to reconsider actions such as Roth conversions that may now have greater appeal and your estate plan which may need to be altered, particularly if you are leaving retirement assets to a trust. Though passed to little fanfare at the end of the year, the SECURE Act is not simply a year-end tax extender; its provisions are permanent and are likely to have a lasting impact on how you plan for retirement and beyond.