Crypto has a low correlation with stocks. What does that mean?

Mining rig in Norilsk (photo by Andrey Rudakov)

© 2021 Bloomberg Finance LP

Stocks, bonds, real estate, commodities. Bitcoin.

Bitcoin? Is cryptocurrency an asset class deserving of a place in every endowment and retirement portfolio?

There is now being built on Wall Street a modern portfolio theory of bitcoins: elaborate demonstrations that a dose of virtual currency will enhance the return or reduce the risk of a portfolio. Be prepared to be bombarded with Sharpe ratios, correlations and optimum allocations.

It could be that all of this fancy arithmetic is proof of virtual currency’s legitimacy. Or it could be nothing but the sign of a top.

Here, I will present the cases for and against an allocation to bitcoin in an investment account, while endeavoring to take a neutral position on where the price of this asset is headed. It’s a 50-50 proposition. Virtual currencies might prove their worth competing against debased fiat currencies, sending bitcoin to $400,000. Or they might be destined to go the way of the South Sea Bubble.

Bitcoin has seen three phases in its 12-year life. The first was Silk Road: a payment mechanism, a Western Union for drug deals. The second phase was speculation. Speculators bought at $570 and sold at $5,700 to another bunch of speculators, who bought at $5,700 and maybe would have sold at $57,000 if the opportunity hadn’t been so fleeting.

MORE FOR YOU

Now we are in the third phase: institutional. August entities like Fidelity, BlackRock, J.P. Morgan and MassMutual are joining in as custodians, portfolio managers or cheerleaders. Indeed, maybe we should include Coinbase on our list of venerable institutions. The ten-year-old trading venue for cryptocurrencies presides over $90 billion in assets and is about to go public at a valuation rivaling Charles Schwab’s.

The institutional fans come equipped with statistics. At heart, modern portfolio theory is just the old eggs-in-one-basket adage dressed up in mathematical terms. The reason to diversify, MPT says, is that you can get the same return as on a less diversified portfolio but with less volatility, or, equivalently, keep the volatility constant while getting magnified returns via some leverage.

$100 grew to…

Forbes

One of the statistics trotted out in this exercise is a ratio popularized by economist William Sharpe. It compares returns to volatility. The higher your Sharpe ratio, the more you’re earning at any given level of risk. What do you know? Cryptocurrency has a fabulous Sharpe.

Bitcoin is fearsomely volatile, but it has more than made up for that with appreciation. The Coin Metrics Bletchley Index clocks bitcoin’s Sharpe ratio over the past five years at 1.6. That compares (per Morningstar) with 1.1 for the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund, which is about as diversified as you can get using stocks and bonds.

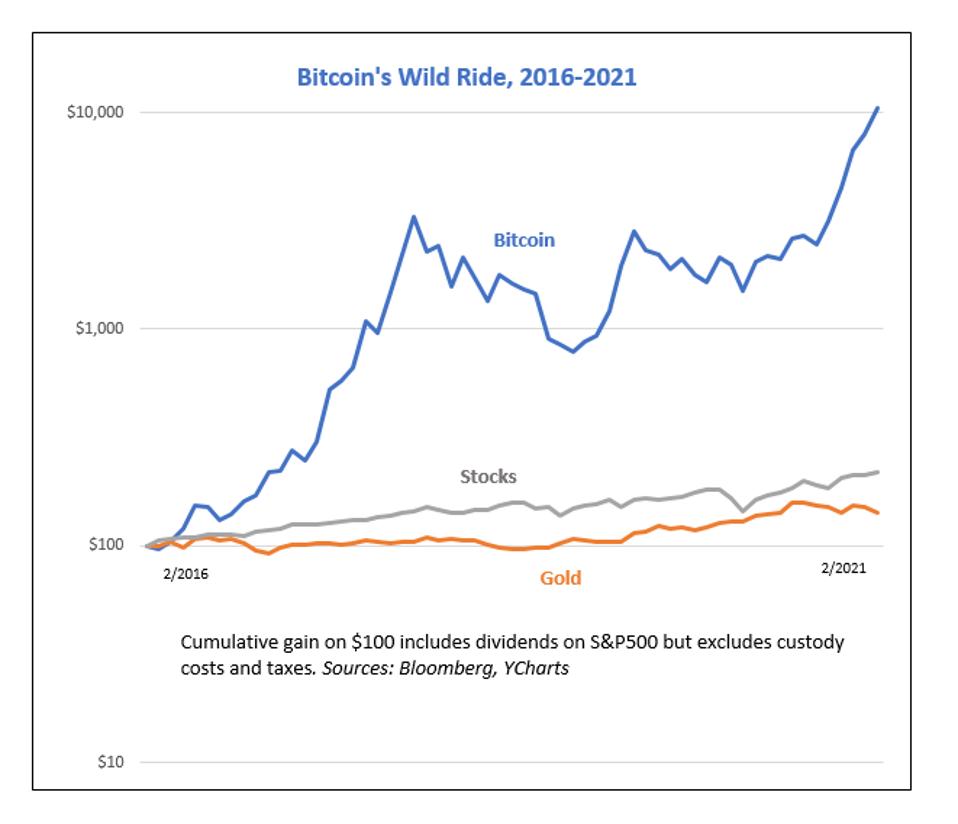

If you could invest with hindsight, you’d go back in time, put 100% of your money in crypto and hold tight to the roller coaster. Over five years you would have multiplied your cash 105-fold (see chart).

No institution, at least not the ones cited above, advocates a 100% allocation to crypto for a retirement portfolio. So now we get into the next round of MPT statistics, correlation coefficients. These are used to make the case for putting a little bitcoin in a portfolio that consists largely of a sedate balanced fund.

The correlation between two series of historical returns measures the degree to which the two assets track one another. A correlation of 1.0 means they march in lockstep. A 0.0 reading means they aren’t connected. The whole point of diversification is to put together a mix of different assets that have low (or negative) correlations with one another. The case for throwing a few real estate investment trust shares into your asset mix is based on correlations: If inflation kills your bonds, it might help your equity Reits.

This is why you hear the salesmen for various alternative assets, like hedge funds, boasting about low correlations to the stock market. Sometimes overlooked in this correlation game is a crucial assumption, that the second asset has a good expected return. If all you want is a low correlation, after all, you could put half your money in the S&P 500 and half in lottery tickets.

On this score bitcoin performs terrifically. Or, to be a little more careful with our language, it has performed terrifically. Over a long stretch it has, unlike lottery tickets, delivered a positive return, and most of the time it goes its own way, oblivious to the stock market.

VanEck Associates, a vendor of exchange-traded funds hoping to get approval for a bitcoin fund, calculates the long-term correlation between bitcoin and the S&P 500 to be a tiny 0.01. If that relationship continues, bitcoin would be a great diversifier in a portfolio containing stocks. One of VanEck’s white papers concludes: “A small allocation to bitcoin significantly enhanced the [hypothetical] cumulative return of a 60% equity and 40% bonds portfolio allocation mix while only minimally impacting its volatility.”

To put this in MPT terms: You can boost a portfolio’s Sharpe ratio by adding crypto to it. But there are two reasons to hesitate.

One reason is that bitcoin’s history is short. It is one thing to look back on a century of history for stocks and bonds and draw conclusions about how much return and how much volatility you can expect from them. It is quite another to extrapolate anything from the freakish first decade of a virtual object.

Bitcoin appears on the 6-cent mark at the August 2010 starting point in Bloomberg’s price chart. Since then it has appreciated 80 million percent. It it were to repeat that rate of climb for a decade, the market value of all bitcoin now circulating would be $370 quadrillion.

Quadrillion? That’s more than the market value of the entire solar system. And yet it’s the feverish history, not a plausible future, that plugs into the formulas for Sharpe ratios, correlations and optimum portfolios.

The other matter gets to the nature of wealth. Most assets are productive, and their worth is related to how much they put out. A bond or a share of stock is a claim on the output of things like cement mills and restaurant chains and vaccine patents. A bitcoin doesn’t produce anything. When you own one you possess nothing but a string of numbers. It’s valuable only because other people want it.

To be sure, you could almost level the same accusation at gold, whose value in jewelry and manufacturing is peripheral to its current price. You could certainly make it against the U.S. dollar, which produces nothing when it is not in motion. Bitcoins, moreover, are by nature limited in quantity. Dollars are not; the government is about to print 1.9 trillion of them in order to make people feel better.

I will conclude by citing comments from the two opposing camps. Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou is a global markets strategist at J.P. Morgan. Says a Morgan research note: “He believes that the adoption of bitcoin by institutional investors has only begun compared to holdings of gold.” He may be right; bitcoin’s spurt since September seems to have taken the shine off bullion.

And then there is this, from James Grant, writing in his Interest Rate Observer: “The bitcoin bubble, one of history’s biggest, has naturally ensnared the who’s who of established finance. Wherein lies the trouble.”

As I say, it’s a toss-up who has the better argument here. Maybe you should own a few of those number strings. But don’t let wishful thinking—gee, I should have bought that five years ago—cloud your mind. Here, more than anywhere, applies another Wall Street adage: Past results are no indicator of future success.

Related story: Guide To Cryptocurrency Taxes