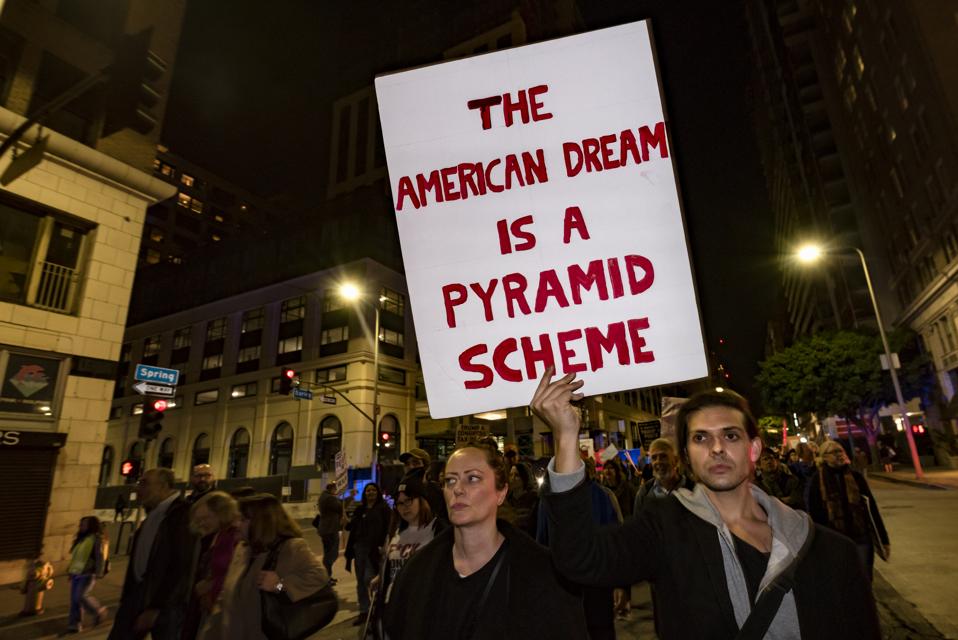

People take part in a protest against the Republican tax bill in Los Angeles, California on December 4, 2017. Democrats and many economists warn that the GOP tax plan gives large tax cuts to corporations and the wealthy and will hurt middle class

NurPhoto via Getty Images

The most obvious parts of financial inequality are income and wealth. A small group makes astoundingly larger sums than most, has vastly more wealth, and keeps getting wealthier through thick and thin, even when remembering the global financial crisis.

There is another part of inequality that is harder to see: taxation. It becomes obvious in some moments, like with the 2017 tax cut legislation that benefited the wealthy at the expense of everyone else. Or with reports like one from ProPublica that low-income people getting the Earning Income Tax Credit on their federal tax filings were more likely to be audited than someone making $400,000 a year. Officials find it much easier to show they’re following up on lost revenue by pursuing those who don’t have the resources to necessarily know if they’re filing correctly or to question or fight back when challenged.

But those are points. The full picture—the graph of all the points, if you will—can be seen in just that, a series of graphs created by the New York Times in an opinion piece by David Leonhardt. You’ll have to go to the piece to see it, but, in short, there’s an animation based on new analyses from a book, The Triumph of Injustice, researched and written by two UC Berkeley professors, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman.

The analysis looks at the total tax rate people pay, between local, state, and federal and including not just various income taxes, but payroll ones as well. Total taxes as percentages of income are shown across all income brackets. The income grouping appears by deciles of the population up until the 90th decile. Then the graph shows the 95th through 99th, the 99.99th, and then the top 400 wealthiest.

As you scroll through the article, you see how the tax rates have changed by decade. In 1950, the top 400 wealthiest had a tax rate of 70%. At the lowest level, it’s about 17%. Then the line of rates starts to thrash about like a snake in pain. It eventually begins to level out in 2006 and by 2018 shows a most peculiar shape. Those at the lowest level—the ones that often you hear people disparage as not paying taxes, when that means federal income taxes, not all the other types—see a rate about 26% or 27%. For the 400 wealthiest, the rate was 23%, lower than any other income group.

Today, the best way to ensure the lowest total tax burden is to be wealthy. Your income is likely from partnerships, capital gains, and other sources not subject to payroll taxes. You have access to resources that can significantly lower your tax burden. Congress passes laws to extend and protect your wealth (because you offer so many opportunities for campaign contributions). So, you pay less as a percentage even as you make far, far more.

(By the way, a couple of years ago, Saez and Zucman worked with Thomas Piketty to accumulate data that informed an income gain graph in which it was clear that those at the very top of the economic pyramid saw an average 7% annual income growth between 1980 and 2014. About 75% of people saw an annual growth around 1%.)

There are a number of implications of the tax issue:

- The less money you make, the more impact the percentage paid in taxes has because it leaves you with much less to meet financial obligations, adequately save for the future, or pay for such things as education, healthcare, and housing, all of which rise in price much faster than inflation.

- The expectations of what ordinary people are supposed to manage—largely flat wages, increased demands to provide their own retirement, less help to get kids through college or trade school, bailouts for banks while millions lost their homes in foreclosure as a result of the economic collapse, and spiraling housing costs—continue to expand.

- By reducing the tax burden on the wealthy and corporations, especially through highly increased deficit spending, government has left the ultimate need to make up the shortcoming to those who are less well off with the GOP common suggestions that it should be necessary to cut Social Security, Medicare, and other social welfare programs, for which people are paying those payroll taxes. The result would be continuing to bring in the revenue but divert it from popular programs to further underwriting the cost of tax cuts for the wealthy.

Put it all together, and you can see that income inequality increases by getting most people coming and going.