Chicago River with boats and traffic from above in the morning

Getty

In response to my latest article on Chicago’s underfunded pensions, a commenter at my personal website shared a link to the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability to affirm his view – and that of many others – that the cause of the the underfunding is simply the unconscionable failure of the city to pay its contributions. The article in question dates to this past January; titled “Chicago’s pension crisis isn’t really about pensions — it’s about debt,” it makes the claim that

“By far the largest reason for Chicago’s level of pension debt is that the city has simply failed to pay what it owes,”

which it backs up in part with a chart showing that the pension normal cost, or annual new benefits accrual, is relatively stable between 2017 and 2030 while pension payments balloon – a statistic that’s true enough but doesn’t provide any evidence one way or the other regarding a claim that boosts in benefit provisions in past years play a role because that’s all now baked into the current and future normal cost.

But beyond that, it attempts to prove that the cause of the crisis is city underpayment with the same recitation we’ve heard before: the city hasn’t paid its required contributions. The author, Daniel Kay Hertz, provides a chart which looks quite a bit like my own graphic from back in January (though his chart starts only in 2008, uses some different timing, and combines all plans, while my analysis only included the largest Municipal Employees’ plan), in which I demonstrated that it’s simply an unhelpful, trivial statement that the city didn’t pay its required contributions, when those contributions themselves grew unsustainably. Hertz’s chart shows an increase of 150% (in nominal dollars) from a bit less than $1 billion in 2008 to nearly $2.5 billion in required contribution in 2017.

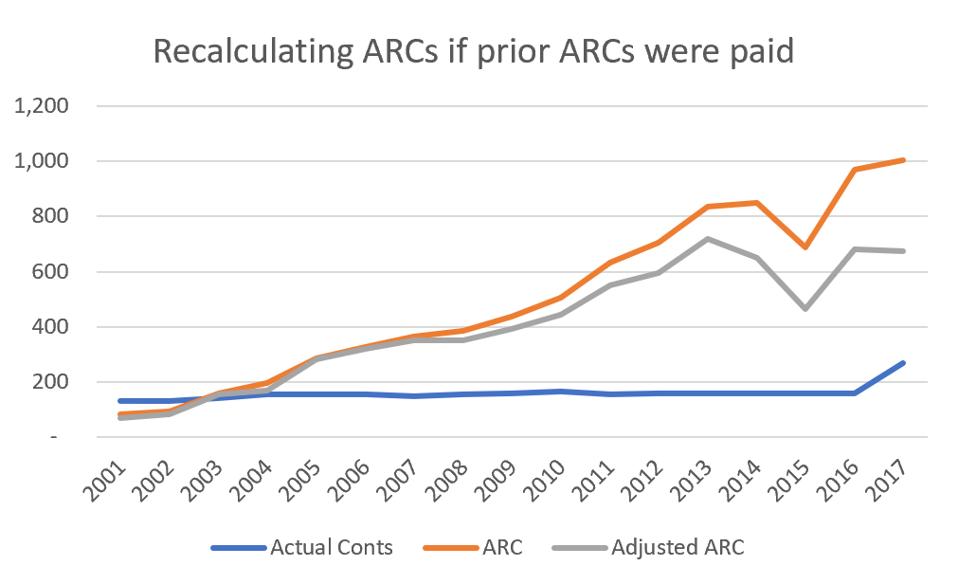

And, as a bit of a refresher, here’s my calculation from January of the Municipal required contributions recalculated to remove the effect that each year’s unpaid contributions are, in part, added to the following year. The bottom line remains that, looking at this chart, it’s plain to see that, had the city been paying the required contributions according to the actuary’s formula, we’d be experiencing complaints that the size of those contributions was spiraling out of control – and (again, go read my prior linked article) even paying those contributions would have left the Municipal plan (again, the subject of my prior analysis) at only about 50% funded.

History of ARCs 2001 – 2017

own work

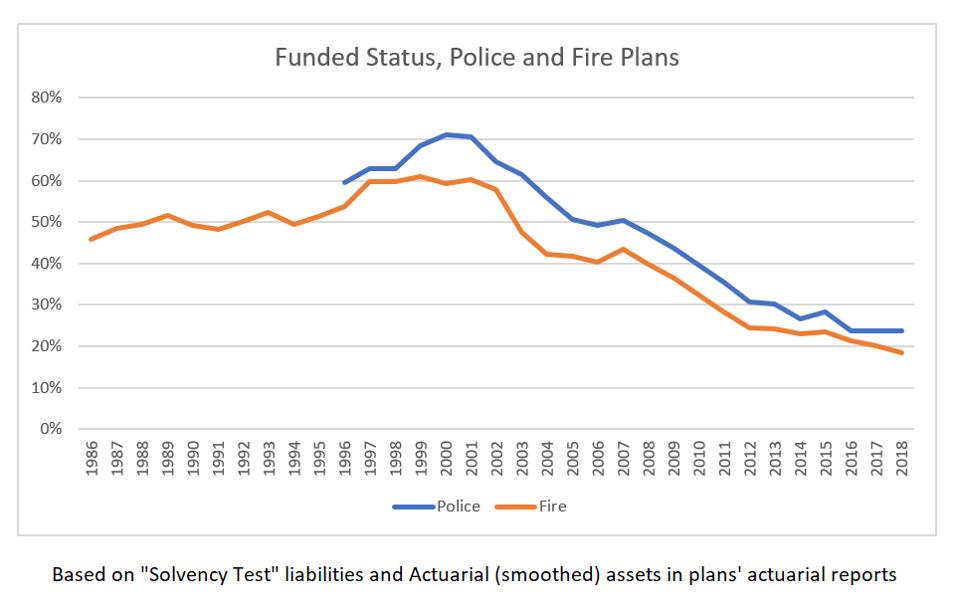

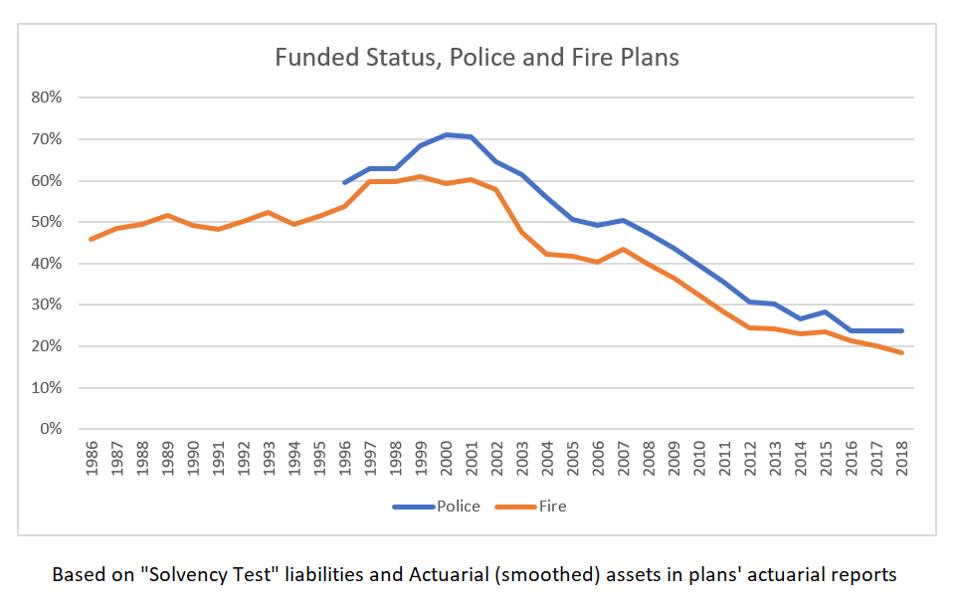

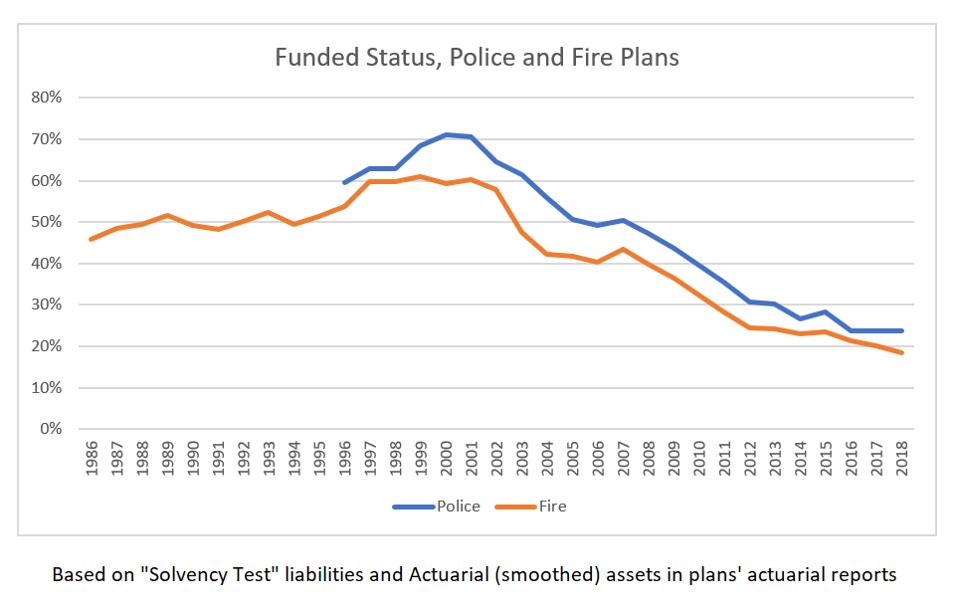

But that’s only the Municipal plan; without engaging in the full reconstruction (and FOIA requests) necessary to recreate the above chart, I have pulled together some basic data for the Police and Fire plans.

Chicago Police + Fire pensions’ funded status history

own work

Chicago Police + Fire pensions’ funded status history

own work

In my January analysis, I sought to answer the question, “how did the Municipal Employees’ plan’s funded status drop so dramatically from its peak of nearly full funding in 2001?” But neither of these two plans ever made it as high as that – while that same year was more-or-less the peak funding year for both of these plans, the highest funded status these plans ever attained was 71% in 2000 – 2001, for the Police, and hovering-at-60% from 1997 – 2001, for the Fire plan.

Funded status, Chicago Police and Fire pensions

own work

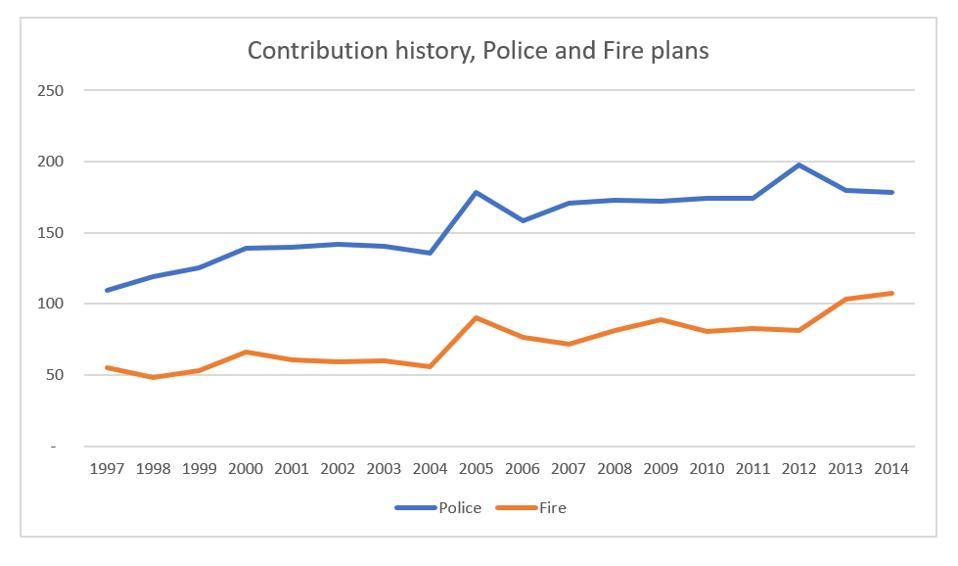

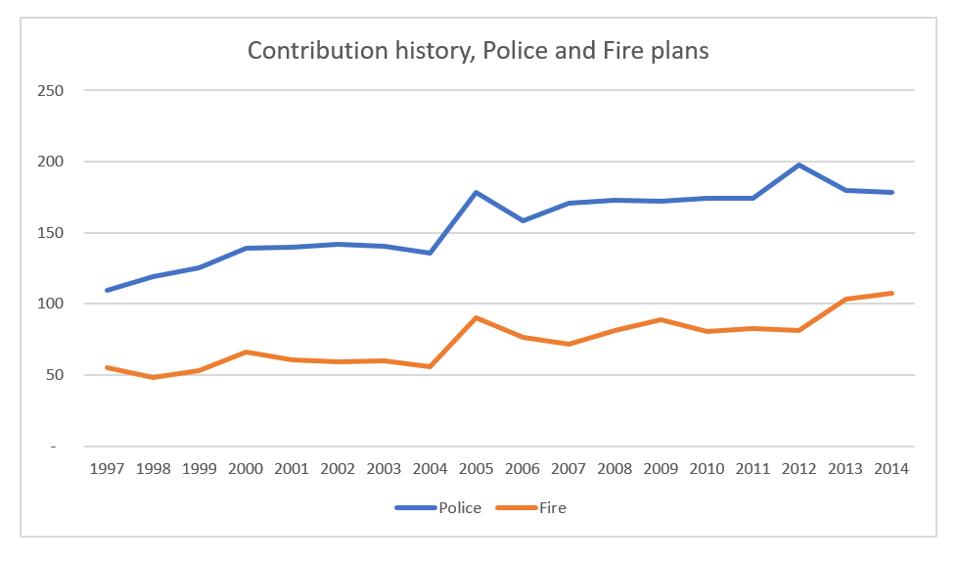

At the same time, actual city contributions are likewise available in the posted-online reporting going back as far as 1997. (Small disclaimer: before 2006, this includes a contribution for retiree medical, but this is a very small piece of the total.) Here I’m only showing contributions prior to the implementation of the “ramp” in 2015, to get a better understanding of past history and avoid the short-term distortion.

Police and Fire pensions contribution history, in billions.

own work

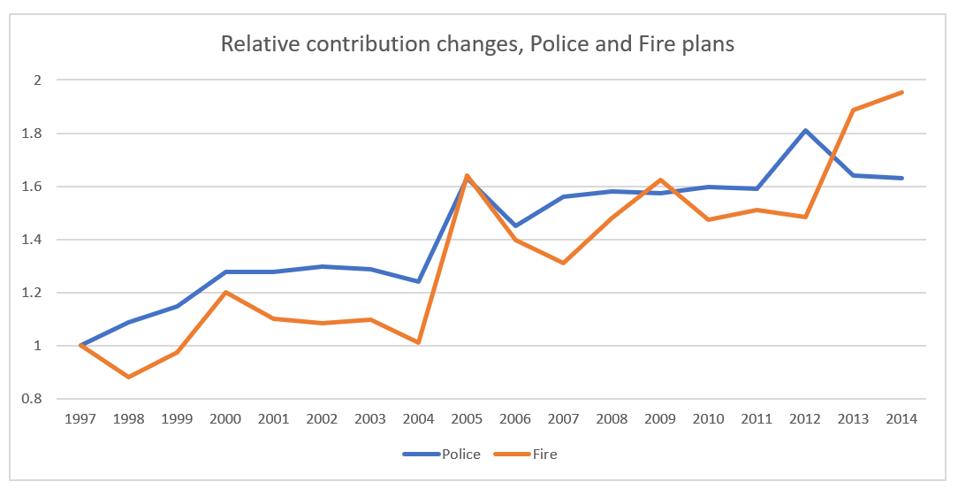

Chicago Police and Fire pensions’ contributions relative to 1997

own work

Chicago Police + Fire pensions’ contribution history 1997 – 2014

own work

Looked at in terms of relative changes since 1997, the Fire plan’s contribution nearly doubled, and the Police contribution increased by 63%. Yes, there was some fluctuation, but no “contribution holidays” in the sense of entirely failing to pay contributions. In fact, whether by coincidence or by design, over this 18-year period, for both plans, whether considering the total sum in nominal amounts or adding in expected asset returns, the contributions very nearly match the amounts as if the city had increased their contributions by the expected annual increase in payroll (that is, using the assumed 3.5% for Fire and 3.75% for Police in the 2018 valuations) – which is not a surprise given that the contributions were based on a “multiplier” approach that should increase in this fashion, but goes against the narrative of contribution cheating.

Now, again, there are multiple factors in move from low to the present catastrophically-low levels of funding: demographic impacts, benefit increases, and the relentless impact of asset losses and assumption and experience losses, in a plan where an asset return rate as high as 8% make the plan very vulnerable when the asset return isn’t achieved. (And, at the same time, the Municipal Employees’ plan achieved its short-lived almost-full-funding with a combination of both very favorable asset returns and increases in the asset return assumption itself.)

But there is nothing that suggests that in the recent past the city has deliberately shorted the pension plans; clearly there’s no pattern that can tie the crash in funding levels to a decline in contributions.

What the funded status and funding patterns do suggest, however, is that, at their inception and for many subsequent years, these plans were never really intended to be any more than partially funded – and by the time everyone involved acknowledged that, indeed, true efforts at funding were necessary, it was too late to reverse course without contribution hikes at levels so large that they themselves would cause howls from people with competing funding demands.

And, yes, I’ll go there: for years upon years, decades upon decades, the city’s firefighters and police officers bargained for wage and benefit increases via their unions. But they, too, saw underfunded pensions as so thoroughly ordinary and unexceptional that, so far as I can tell, it never crossed their minds to bargain for improved pension funding.

Have I made my case sufficiently well? Tell me at JaneTheActuary.com!