There is a well-known saying, “the map is not the territory,” that metaphorically illustrates the differences between belief and reality. Through our perception of the world, we create a ‘map’ of what we perceive to be reality. However, reality, or the “territory”, exists independent of our subjective experiences. We see as far as getting to the places where we want to go and do not always understand boundaries and directions that our senses do not perceive.

We find a similar conundrum in the estate tax planning world. Well-meaning advisors and their studious clients are not always running the numbers to help ensure that the strategies and techniques they are using will provide the best-expected results. Their maps unfortunately leave a great deal of uncharted territory that can result in negative repercussions in the future.

We have found from years of experience that there is no substitute for taking out a calculator or spreadsheet and reviewing the most probable scenarios (as well as possible and unexpected situations) to determine the expected and non-expected outcome of any given technique in order to produce the most accurate map possible of the estate planning territory.

In addition, many misconceptions are easy to have, given the complexity of the tax law and the impact that multiple influences will have on a given situation.

Some examples of fundamental principles and structural design situations that may be of interest to readers are as follows:

Mistake #1 – I Don’t Have Enough to be Concerned.

Many individuals and married couples believe that because the total value of their assets is under the $11,700,000 per person exemption, they do not have any need to plan for or have a concern about federal estate taxes.

More commonly, individuals or married couples who have approximately one-half or less of the exemption amount in assets and life insurance believe that they do not need to do any long-term planning. These individuals often do not recognize the time value of money and the fact that they continue to save even if they are not actively saving large sums.

The “time value of money” is a term commonly given to the fact that over time and using conventional investment vehicles, the net worth of an individual or entity will grow in a geometric progression.

While the New York Times has reported that it was not Albert Einstein who said, “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.” Einstein likely recognized this principle, notwithstanding that he was reportedly not very materialistic.

The average rate of return for an appropriately allocated investment portfolio in the past 10 years has been approximately 7.28%, after taxes, according to credible literature.

The author’s rate of return on the low-cost periodically reallocated portfolio of mutual funds that was selected in 1999 and changed rarely, and in only minor ways has grown at around 7% on average.

$1 million invested at 7% compounded annually reaches $1,967,151.36 in 10 years, $ 3,869,684.46 in 20 years, $6,612,255.04 in 30 years, and $14,974,457.84 in 40 years. The author commonly tells clients that they can expect the value of their investment assets to double every ten years, which would assume a 7.2% annual after-tax rate of return. The average annual rate of return of the S&P 500, which is what Warren Buffet has advised his wife to invest in after his death has been 10.71% since 1970, 11.83% since 1980, and 10.33% since 1990.

At an average rate of growth of around 10%, $1 million invested today would turn into $2,593,742.46 in 10 years, $6,727,499.95 in 20 years, $17,449,402.27 in 30 years, $45,259,255.57 in 40 years.

Based upon the above, a married couple in their early 70s, who have a combined net worth of $10 million, and who will spend 2% of the value of their assets, may realize a 5% after-tax rate of return on their investments. This is in addition to social security, which averages approximately $35,000 a year for a married couple when at least one spouse was a higher earner, plus any pension or other benefits and earnings from continuing to work. So, after ten years, assuming no further savings, and if the estate tax exemption grows at 2.5% a year (based upon the chained consumer price index that applies to the estate and gift tax exemption), their net worth will be $16,288,946.27 million.

The chained inflation index does not include taxes not directly associated with the purchase of goods and services or investment items, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and life insurance. The chained inflation index typically grows at approximately two-thirds of the average consumer price index – all items, which has been rising at 45.7% (for the consumer price index all items) and 39.7% open (for the chained inflation index) in the last 50 years.

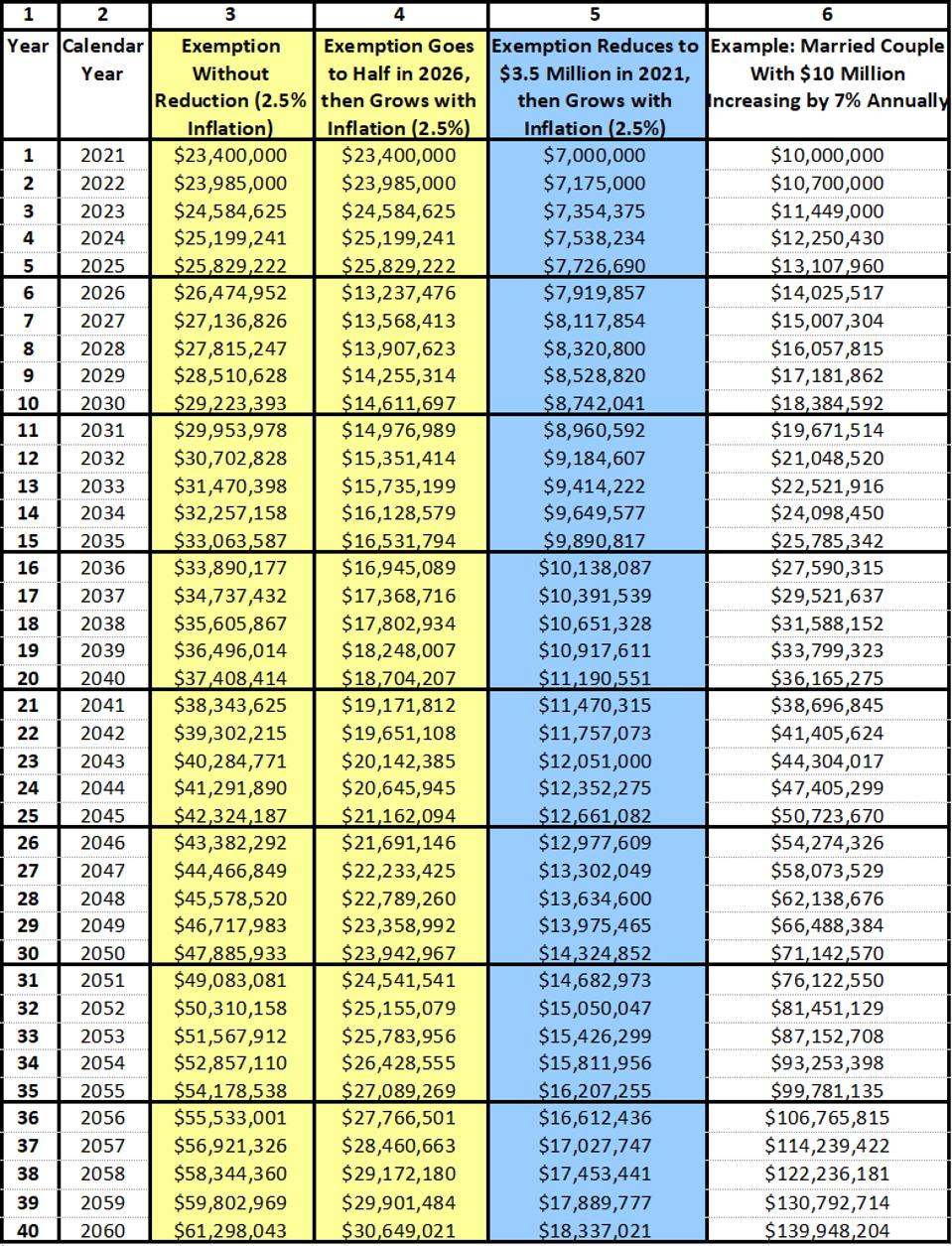

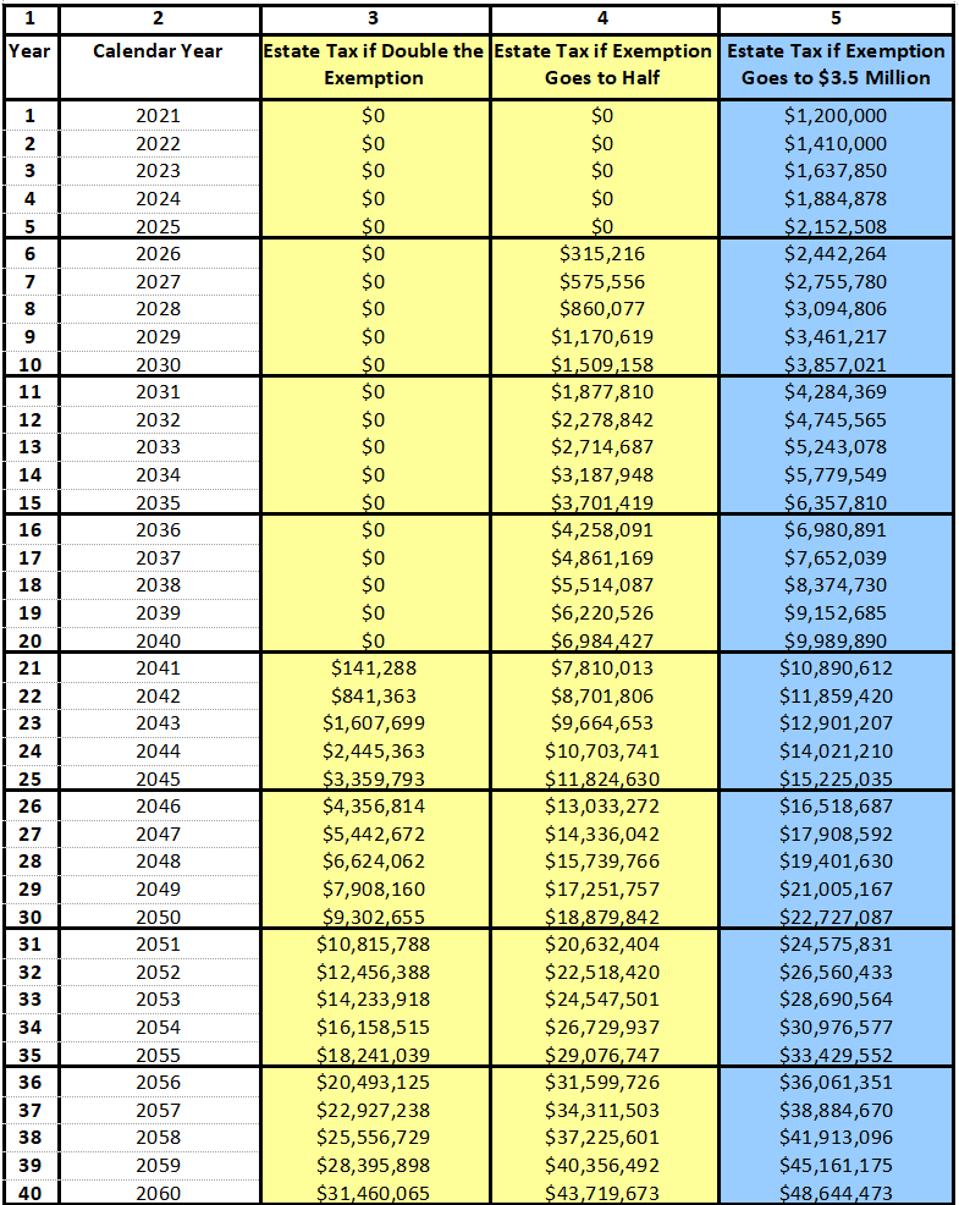

There are three main possibilities that the author cautions clients to be aware of regarding the current federal estate tax exemption. The current estate tax exemption of $11,700,000 per person may continue to grow at 2.5% per year. It may be slashed to one-half of its expected level on January 1, 2026, and then continue to grow at 2.5% a year. Finally, the exemption may be reduced to $3.5 million in 2021 and grow with inflation. An illustration of how these different situations would affect a married couple with $10 million dollars saved is illustrated below. We have produced an easy to use version of the chart below on excel with user interface. Email info@gassmanpa.com and put “spreadsheet” in the subject line and we would be happy to send it to you.

The exemption may be reduced to $3.5 million in 2021 and grow with inflation. An illustration of how … [+]

Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo P.A.

Taking a look at the above chart, which should probably be shared with all married couples with net … [+]

Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A.

For example, assuming chained inflation will increase the exemption amount by 2.5% per year and the couple has $10 million dollars that will increase in value by 7% a year, the estate tax in year 15 will be $6,357,810 if the estate tax exemption goes to $3,500,000 per person, or $3,701,419 if the estate tax exemption is reduced by half in 2026.

This couple would not have an estate tax issue until after the year 2041 if the $11,700,000 exemption is not reduced before then.

Under the Sanders Plan introduced in the Senate with some support in March of 2021, the exemption would go to $3,500,000 effective January 1, 2022.

Taking a look at the above chart, which should probably be shared with all married couples with net worths expected to well exceed $7 million, there is certainly a possible cause for concern. However there are fairly easy ways to handle the planning that does not have to be expensive or restrict the assets that may be needed to support the married couple, and then the surviving spouse, in a reasonable manner.

How Much to Give and When?

Seeing the above numbers can be a sobering experience, and while pessimistic clients may indicate that this result is not likely for a myriad of reasons, it should be recognized that the result is not unlikely. Things will be worse from a tax standpoint if the economics are better.

The question becomes what the married couple or individual can do to alleviate the risk of federal estate tax. Experienced estate and trust planners know to start with the low-hanging fruit, which includes the use of irrevocable life insurance trusts, and sometimes split-dollar financing to enable the couple to access the surrender or loan values of permanent life insurance policies.

Other low-hanging fruit can include a Qualified Personal Residence Trust because the couple can continue to live in their present home without paying rent until many years up the road when they are less active and more able to afford rent. The QPRT can sell the home to buy a more suitable home in the future or use any excess funds to make payments to the grantor that can be used to rent a home or to defray expenses during the possessory term. This is with the assumption that each spouse forms a QPRT, and that one QPRT is for the health, education, and maintenance of the spouse who has a longer life expectancy and will be funded with ownership of one-half of the home. After the possessory term, the other half of the home can transfer to a separate QPRT for the prime benefit of the descendants. Still, the other spouse may be added as a beneficiary to such a second QPRT if formed in an asset protection jurisdiction. And if formed and administered from an asset protection jurisdiction, and the grantor spouse has an unexpected financial need after establishing the trust, as verified by Trust Protectors acting in a non-fiduciary manner.

However, it is noteworthy that homes generally grow in value at a rate much lower than appropriately managed investment portfolios. While the median home may grow in value at a 3-3.5% rate on a national average, your home gets one year older every year and is not always 20 years old. Also, your home will need a roof, occasional pluming, and will have restoration and other expenses that the “median home” does not have.

Approximately 80% of the average home consists of the physical structure, which typically has a useful life of 60 years. Therefore, a $1 million home loses 1.67% of the value of the structure, and may therefore only be growing at a net rate of 2% per year. Nevertheless, if the value of a home will double in 20 years, it can make sense to use a small portion of a client’s estate tax exemption amount now to reduce what will be subject to federal estate tax later.

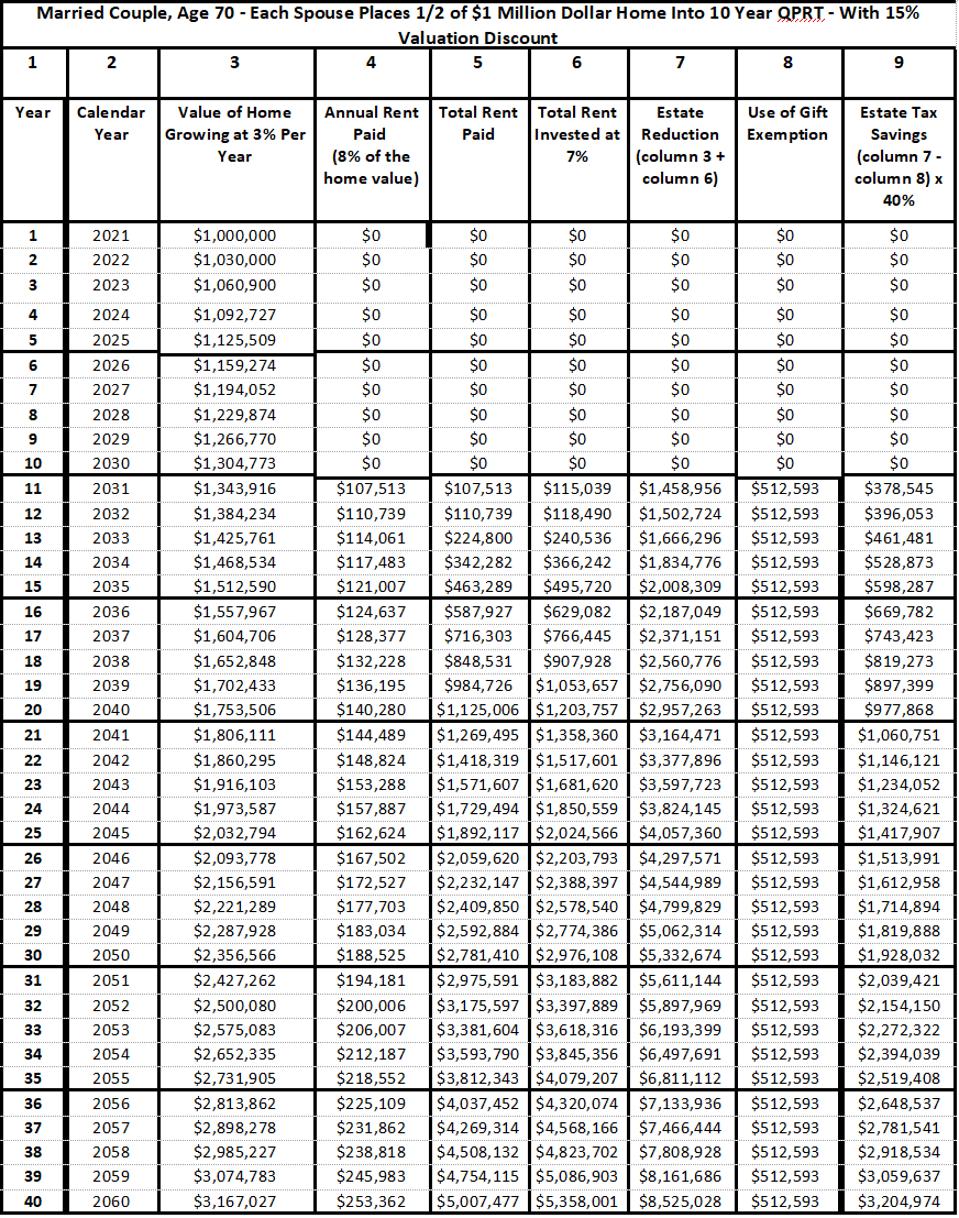

As an example, assume that Mork and Mindy are married and would now be 70 years old. They each expect to live past age 85 and to stay in the home for their entire lifetimes.

Each of them transfers half of the home, worth $1 million, to a 10-year Kuper QPRT. They each take a 15% discount for partial interest ownership, so the total gift is valued at $850,000. Based upon the 7520 rate of 1.2% the remainder value of a ten-year QPRT is $754,420.90. Therefore, the taxable value of the gift is $512,593. Using $512,593 each of Mork and Mindy’s exemptions and assuming the value of the home will grow at a rate of 3% per year, the home will be worth $1,512,590 in 15 years and will have escaped the estate tax system. Any major improvements made on the home are considered a gift to the trust. The amount of the taxable gift would be based on the fair market value of the improvement. Further, assuming that rent rates will be 8% of the value of the home, working Mindy’s estate will be reduced by 8% per year in rent, which could save $598,287 in estate tax if invested at 7% by year 15, assuming that Mork and Mindy do not pass away before the end of the QPRT term.

An illustration of this scenario is depicted below:

Married Couple, Age 70 – Each Spouse Places 1/2 of $1 Million Dollar Home Into 10 Year QPRT – With … [+]

Gassman, Crotty & Denicolo, P.A.

For example, if one spouse dies in year 20 when the house is worth $1,753,506 the total rent that was paid, plus growth at 7% would be $1,203,757. So the two amounts combined would remove almost $3 million dollars from the surviving spouse’s estate, saving over $975,000 in estate tax assuming a 40% tax bracket.

Further, the expectation of having the use of both estate tax exemptions for a married couple does not take into account the possibility that one exemption may not be used in whole or in part. The exemption of the first dying spouse, for example, will only be used to the extent that assets pass to a Credit Shelter Trust or, at least, other than to the surviving spouse. Any excess allowance to be available would be only to the extent permitted under the reportability rules, which do not provide for Consumer Price Index increases.

Examples and discussion may only be the tip of the iceberg in respect to going about “running the numbers” for a married couple who is interested in what to do from an estate planning standpoint. When in doubt, math it out.