By Chris Farrell, Next Avenue

Years of grassroots activism led to the new law saving pensions for union members

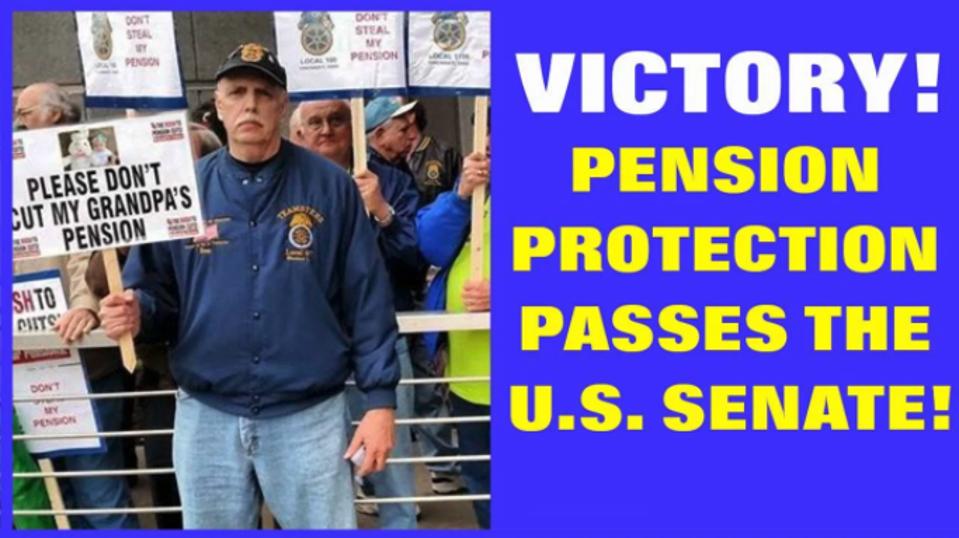

Teamsters for a Democratic Union

Good news on the retirement-income front. Some 1.5 million workers and retirees faced the real risk that their pension incomes would be slashed over the next 20 years or significantly sooner. But the American Rescue Plan Act just signed by President Joe Biden will prevent that from happening.

That’s because the massive legislative package includes the Butch Lewis Emergency Pension Plan Relief Act of 2021. It restores to financial health more than 100 failing pension plans known as multiemployer plans (they covered more than one company’s employees) for union workers. Most notably, the Teamster’s storied Central States, Southeast & Southwest

CSWC

Which Retirees Will Be Helped and Why

Consequently, truckers, bakery workers, plumbers, construction trade workers and others will receive the benefits they were promised based on their years of work. (Butch Lewis, who died in December 2015, was a Teamster and a pension-protection movement leader.)

“I’m ecstatic by the passage of the Butch Lewis Act, and it’s all because of the activists,” said Karen Friedman, executive director of the nonpartisan Pension Rights Center.

Among those activists were six retired Teamsters from Local 120 with membership in Minnesota, Iowa, North Dakota and South Dakota.

MORE FOR YOU

Eight years ago, Steve Helle, Sam Karam, David Kremer, Randy Furst, Paul McDaniel and Robert McNattin met at a coffee shop in St. Paul, Minn. to talk over the precarious finances of their union’s pension fund. Each threw in $20 during the meeting and formed the grassroots organization Defend Our Pensions-Minnesota.

Membership now totals more 1,000 and retirees from other mostly old-line unionized industries formed similar grassroots organizations.

“It’s hard to believe what we, along with other retirees like us from the region served by the Central States pension plan, have accomplished; the friends we have made, the financial support from our fellow retirees, and, I must say, the regard in which we are held by the labor movement nationally and in Minnesota, and by our elected public officials,” wrote Robert McNattin, now 82 and co-chair emeritus of Save Our Pensions-Minnesota, in an email. “All of this has occurred AFTER we had retired and were no longer active Teamsters.”

Why are there multiemployer pensions? It’s because union workers in industries like trucking, ironworking, carpentry and similar skilled occupations often change employers while staying with the union during their careers. So, unions set up pension plans funded by multiple employers and union members allowing workers to accrue benefits while going from job to job.

Why Government Stepped In For a Rescue

There are some 1,400 multiemployer pension plans covering about 11 million workers in the United States. More than 100, including some of the biggest, had fallen deep into a financial hole.

“They were too far gone for corrective action enough to solve the problem,” said Jean-Pierre Aubry, associate director of state and local research at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College: “There was no way the problem would be solved without some infusion of cash from the government.”

Several factors conspired against these financially troubled pension plans and their workers. Among them: deregulation, declining private-sector union membership, shrinking industries, bankruptcy and companies exiting the plans for a relatively modest price.

The funding of the most critical plans worsened following the two financial crises after the turn of the 20th century. Meantime, the program run by the federal government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), to backstop defunct multiemployer pension plans, was also underfunded. (The PBGC is also the backstop to traditional employer pension plans.)

A vicious downward cycle set in.

Gordon Hartogensis, director of the PBGC, testified before the Senate Finance Committee in 2019 about the risk of plan insolvency for some 1.4 million participants in roughly 125 plans within 20 years.

“That means plan participants will see a substantial reduction in the benefits they receive — mere pennies on the dollar. The backstop that hardworking men and women had been depending on for a secure retirement — and to help support themselves and their families — simply won’t be there,” he said. “Let me be as clear as I can. Unless Congress acts, participants in insolvent plans will receive next to nothing. A typical retiree with thirty years of accrued benefits would receive only about a hundred dollars a month.”

That devastating outcome won’t come to pass, due to the new law.

How the Shaky Pension Plans Will Be Shored Up

The Butch Lewis part is multi-layered, but here is the key shift: The U.S. Treasury will establish a special financial assistance program administered by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. Plans that meet the bill’s insolvency-at-risk measures will receive a cash payment sufficient to pay all promised benefits through 2051. Estimates are that between 185 and 225 multiemployer pension plans will receive grants totaling $86 billion.

Friedman of the Pension Rights Center says the new law will also restore benefits to tens of thousands of workers whose pensions were cut following legislation from 2014.

“Using the PBGC as the way to support the worst-off plans is the right vehicle,” said Aubry. “The PBGC is there to protect beneficiaries.”

The Next Retirement Problem to Solve

The years of grassroots activism by mostly retirees working to save their pensions is admirable. But their dogged determination raises an intriguing question: Could their energy be tapped to put pressure on Washington to finally fill in the biggest hole in America’s retirement savings system?

That’s the sad problem of millions of U.S. workers who have no employer-sponsored retirement plan.

Only about half of private-sector employees work at companies that offer a retirement savings plan. Most of the “uncovered” have jobs at smaller businesses, earn low wages and don’t have any savings when they retire.

One possible remedy is easily at hand, though.

Several states have created automatic-enrollment retirement savings programs for private-sector workers lacking access to other workplace retirement plans. Oregon, which is one of them, recently published a study by four economists concluding that its program had “meaningfully increased employee savings.”

Some retirement and employment analysts believe the federal government could take the success from the state laboratories of democracy and rapidly create a national retirement savings system.

But a policy lesson from the multiemployer pension rescue is that nothing happens in Washington, D.C. without pressure.

Friedman thinks the time to fix America’s broken retirement system is now. “We need to come up with a system that works. This has to be a big focus of the country,” she said.