CHICAGO – MARCH 16: A Chicago Police boat patrols the Chicago River in Chicago, Illinois on March … [+]

Here are some excerpts of interest from a May 26, 1965 Chicago Tribune story, “Police, Fire Pensions Tabled”:

“Three important police and firemen’s pension bills appeared defeated today but efforts may be made to revive one which would consolidate 335 pension systems outside of Chicago. . . .

“Robert Erickson, a spokesman for the Civic federation, Chicago taxpayers’ organization, was happy when two tax-increasing bills were tabled by their sponsors.

“One would have required a property tax boost to yield 90 million dollars in the next 10 years to build up reserves for the Chicago police pension fund. Erickson said this fund is in good shape, now 35 per cent of actuarial requirements, and steadily increasing. . . .

“Supporters of the consolidation bill for municipalities with 5,000 to 500,000 population cited figures showing how far these pension funds are lagging behind Chicago’s 35 per cent in relationship to the actuarially sound figures.

“For police pension funds, in Cicero it is 4 per cent, Decatur 6 per cent, Elgin 3 1/2 per cent, Glencoe 11 per cent, Springfield 7.4 per cent, Forest Park 8 per cent, Rock Island 8 1/2 per cent, Freeport 9 per cent, Galesburg 12 per cent, Moline 4 1/2 per cent, Quincy 5 per cent, Pekin 9 1/2 per cent, Waukegan 8 per cent, and Peoria 10 per cent.”

And the reasons why the bill failed are much the same as why the recent consolidation law only consolidates the pensions’ asset management, not the overall pension administration, that is, the fact that the high expenses of these small local pensions are due to board members, administrators, and lawyers getting generous paychecks for their work.

But here’s what’s astonishing about this article on the pensions’ funded status: the fact that the 35% funded status for Chicago’s pension plans is treated as being “in good shape” — at least in comparison to cities where there is effectively no advance funding at all, but rather, pensions were run on a pay-as-you-go basis with a nominal reserve fund.

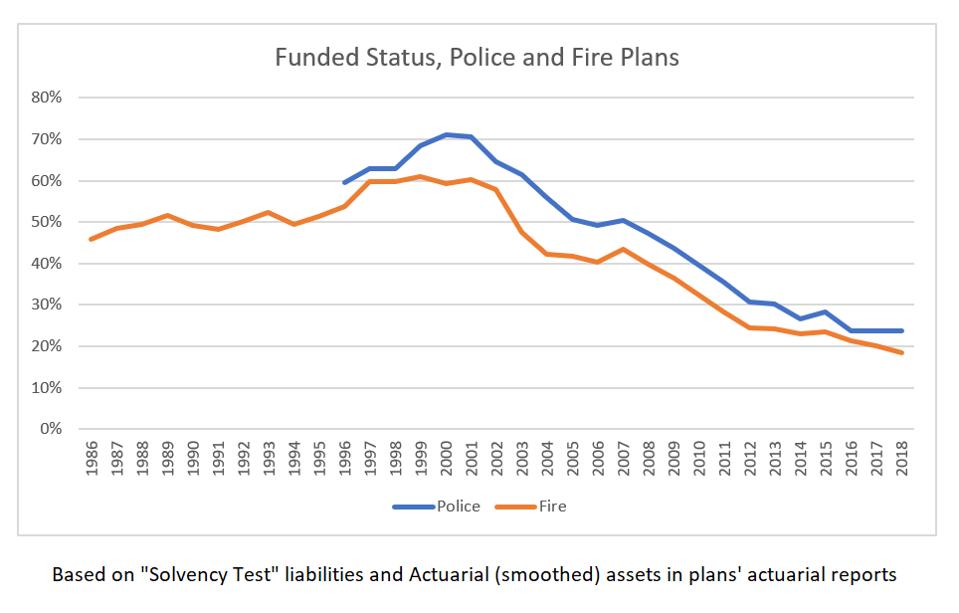

Now, that was 55 years ago, and in the meantime, the city and the state both began to accept the concept that not just private sector but also public sector pension plans should be funded in a proper actuarial manner, that the pension fund should be more than just the single-digit percentage funds listed above. And indeed, by the time the oldest available records are available online for the Firemen’s pension fund and the Policemen’s plan, the funds had made at least some progress above this 35% (though to what extend this is due to an increase in contribution levels vs. a move to riskier assets and higher investment return assumptions isn’t possible to say).

History of police and fire funded status

At the same time, the pension (asset-only) consolidation wasn’t passed after so many years due to a new resolve to fund pensions but in part due to a promise of something-for-nothing (higher asset returns and lower expenses) and due to pressure placed on local communities due to the 2011 “pension intercept” law by which the Illinois comptroller withholds state funds from towns and cities which don’t properly fund their pensions to a “90% in 2040” target.

And here’s the challenge that I am working out for myself and will pose to readers as well:

It will not surprise readers that one of my objectives in writing on this platform is to play a role in making some progress, however small, towards pension reform in those states and cities (Illinois and Chicago, yes, and those others with dreadful funding as well) with atrociously-poorly funded public employee pensions.

Yet the most obvious rejoinder from any worker or retiree at risk of having their pensions cut (COLA or guaranteed fixed increases curtailed, generous early retirement provisions removed, accrual formula reduced for future accruals) is a simple one: public pensions have been underfunded by modern metrics, for generations, essentially since the inception of those pensions. (See here and here for the early history of the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, which was much the same.) Why should this generation be the one to suffer from the obligation to bring the plans up to funded status — either as pensioners or participants with benefit cuts, or as taxpayers?

To be sure, the politicians repeating over and over again “pensions are a promise” don’t explicitly say this. When Mayor Lightfoot acknowledges that the city will be hard-pressed to make its required payments in to the pension funds and still reach her other goals for city services, but can’t voice any solution other than stumbling around various ways of saying, “this is hard” (for instance, back in August), this is surely what’s underlying her statements (or lack of meaningful statements): “it’s unfair that the rating agencies now think pensions should be funded.”

And I’ve written in the past on why it actually does matter to pre-fund pensions, but it is admittedly not easy to persuade, well, anyone, that the right thing to do with whatever tax money you can scrape up is to put it in a pension fund, when you’ve got people clamoring for it to be spent on education or mental health or housing or any number of other items on a wishlist.

Prizker regularly says that there’s no point in expending political capital on a pension reform amendment because it wouldn’t have the public support it needs ot pass, and I regularly complain that his willingness to expend not just political capital but also cold hard cash on his graduated tax amendment shows that it’s really about his priorities, but it also does fall to the rest of us, in those states and cities with these woefully-underfunded pensions, to make the case that it does indeed matter.

What do you think? Share your thoughts at JaneTheActuary.com!