Getty

Forget “OK Boomer” memes. The generational conflicts are really going to heat up when the next recession hits. Gallup polling shows increasing numbers of Americans are worried about a recession. Global trade numbers released Monday and the third quarter report from the International Monetary Fund indicate people may be right—there are serious signs of an economic slowdown. It is clear that many Millennials will fare poorly in the next downturn, with student debt and all that. But few have asked what will happen to Boomers in the next downturn.

Our numbers find that workers aged 55 to 64 are more economically vulnerable today than they were before the last recession. More working Boomers have fragile finances, shrinking retirement and health benefits, and lingering wounds from the Great Recession have yet to heal. The effects of older workers increasing vulnerabilities could be historically significant. Since older people are more likely to vote, economic insecurity among older workers could affect the 2020 Presidential election.

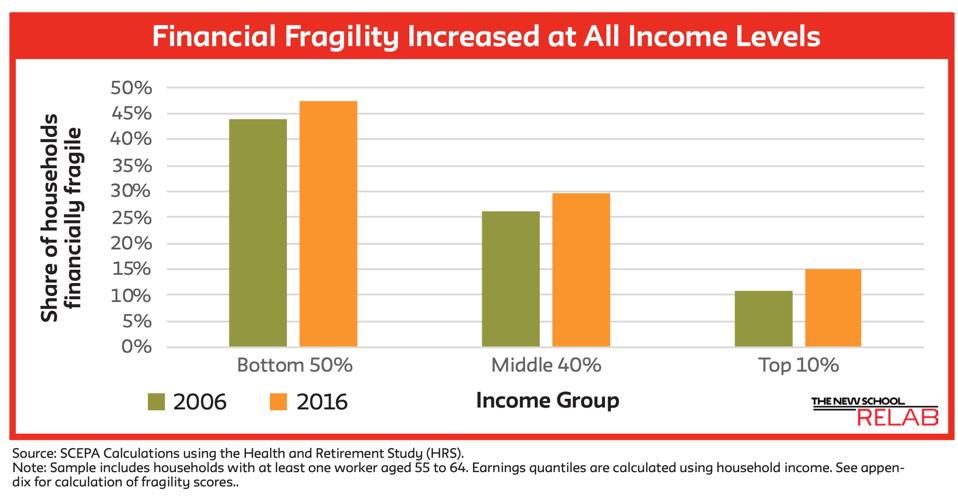

Most notably, financial fragility among older workers is higher now than back in 2006. The share of older workers who are financially fragile rose from 31% in 2006 to 35%t in 2016. Things are much worse for low-income elderly. The share of lower-income older households with low asset levels or high debt rose from 42% to 46%. (Note: 2016 is the most recent year for which data is available; see appendix here for methodology).

Older workers’ financial fragility

A combination of factors cause the increased financial fragility. For some families, financial fragility just means having too few assets to cushion a lost job. But many Boomers simply have more debt than previous generations caused by sluggish wages and bank, broker and other debt solicitors. We have seen a decades-long rise in borrowing at older ages, driven not only by mortgages but by credit cards, auto loans and even student debt.

During the post-recession economic expansion, older workers’ financial situation improved—but not enough to get them back to where they were in 2006. Another recession means millions of older workers will likely face bouts of unemployment. Without sufficient assets to pay debts and get by without a regular paycheck, financially fragile households will suffer more.

When the economy tanks, being older has benefits as well as drawbacks. Older workers tend to have higher job tenure—they have been with their current employer longer—which shields them from layoffs. But when older workers do lose their jobs, they suffer more. Younger workers who lost jobs in the Great Recession on average took modest pay cuts when they found new work. For those in their 50s and early 60s, however, new jobs paid around 20% less. For those 45 to 54, the unemployment penalty was 25%.

The group in their late 40s and early fifties in 2009 is now approaching retirement. Their last recession experience introduces another vulnerability: labor market scarring. Losing a job once makes it more likely to lose one’s job or see a wage cut later on. For millions of Boomers who lost their jobs in the Great Recession, the result has been permanent scarring.

Finally, many older workers are vulnerable because they have lousy jobs with lousy benefits. Our colleagues at Boston College found that one in five older workers has neither retirement benefits nor health insurance, a group that has grown since the early 1990s.

Older workers have also moved into the gig economy, where benefits and job security are scarce. ReLab’s Michael Papadopolous found that the share of workers aged 55 to 75 who work in alternative work arrangements—gigs, on-call work, temporary jobs, etc—increased from 15% in 2005 to 24% in 2015.

In sum, many older workers can expect greater hardship in retirement because of higher financial fragility and lousier jobs. So what do we do about it?

With the rapid aging of the workforce, we need to pay close attention to older workers. Mounting recession fears underline the need for a comprehensive policy approach to protecting older workers. In 1920, the rising share of women in the labor force prompted the creation of the U.S. Women’s Bureau. With older workers becoming an ever-larger part of the economy, we need an Older Workers Bureau to focus on older workers’ issues and devise policies to address them.

Another way to protect older workers in a downturn is to expand unemployment insurance, which many states have cut since the Great Recession. Once unemployed, older workers rely more on unemployment benefits than do younger workers. Restoring unemployment insurance is a direct way to help older workers displaced by the next recession.

Older workers would also benefit from proposals to expand Social Security benefits. Whether or not a recession is underway, no government program does more than Social Security to ensure dignity and security in retirement.