(This story is part of the Weekend Brief edition of the Evening Brief newsletter. To sign up for CNBC’s Evening Brief, click here.)

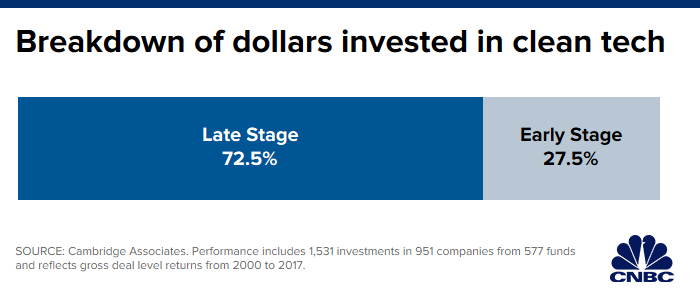

Venture capital funding for clean energy technology companies has declined after years of lackluster performance drove investors to other sectors. But a new fund is making a big bet that it’s possible to back clean tech companies at the earliest — and often riskiest — stages, all without sacrificing returns.

In October, Clean Energy Ventures announced that it raised $110 million for its first fund, which will target “the current capital gap for seed and early-stage investment in promising advanced energy innovations,” a press release said.

The firm’s strategy rests on the belief that without reinventing the wheel, and without compromising returns, it can identify and fund scalable, capital-efficient start-ups that will significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

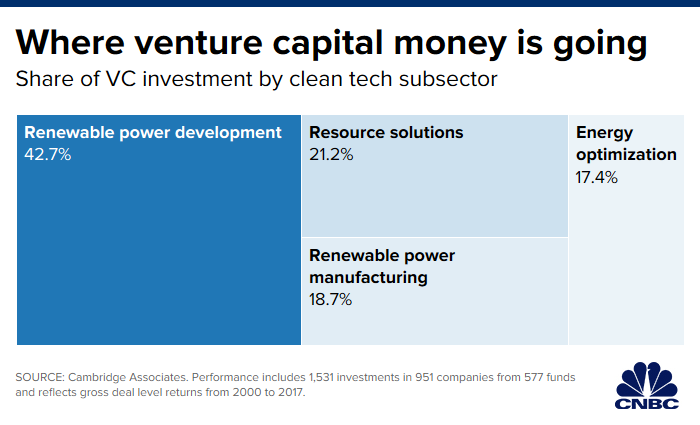

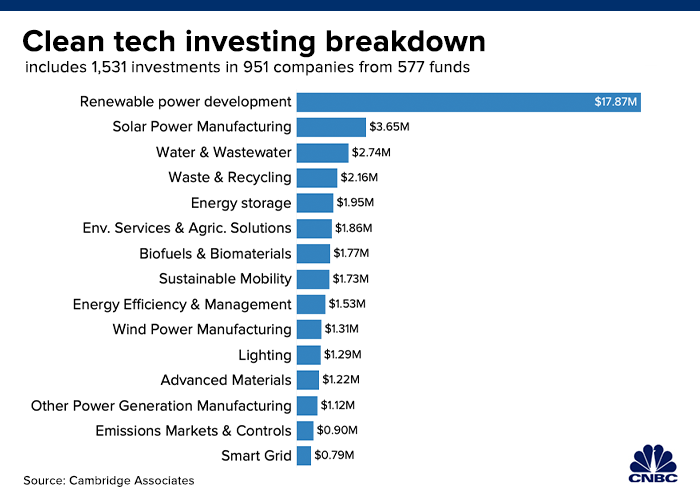

With this influx of capital the fund’s three principles, who between them have backed more than 30 early-stage clean tech companies over their combined 40-plus years of investing, are looking to back companies in areas like energy storage, grid connectivity and clean transportation.

“There’s a valley of death right now. There’s a lot of brilliant technology that’s being built … but to get to a Series A or Series B it’s a long haul,” Clean Energy Ventures co-founder Temple Fennell said to CNBC. “Some people consider us a special forces team that’s brought in with capital and talent.”

Clean tech investing’s boom…and bust

In the mid-2000s, the backdrop for clean tech investing seemed almost too good to be true.

Oil and natural gas prices were rising, which accelerated the demand for cheaper renewable energy. The government began issuing tax credits for alternative sources of power. Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” captured the nation’s attention. Money flowed in as investors looked to profit on the promise of revolutionized industries.

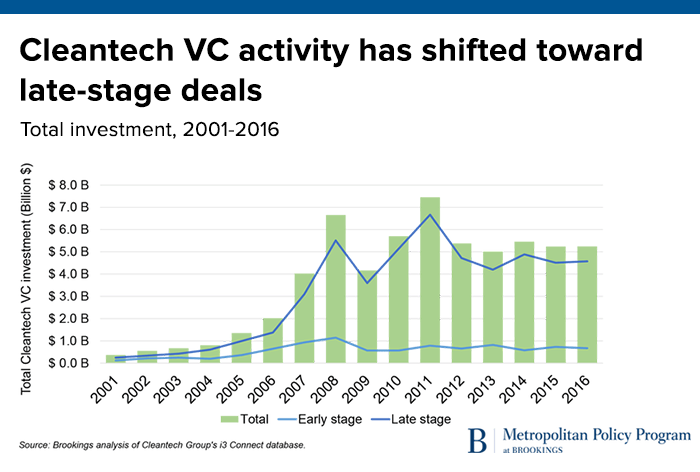

But then the financial crisis hit. It became harder to borrow money. Natural gas prices also dropped, and an oversupply of Chinese-made solar panels flooded the market. Ultimately, more than half of the $25 billion that flowed into the clean tech sector between 2006 and 2011 was lost.

It might seem easy to blame the financial crisis as the primary reason for the failure, but a 2016 research report from the MIT Energy Initiative argued that the majority of companies actually failed for reasons independent of the broader economic backdrop. The venture capital model — where investors supply limited funding upfront and expect relatively fast returns — was not always conducive to the frequently capital-intensive, longer time frame nature of clean tech companies that were trying to reinvent the landscape.

“Cleantech companies developing new materials, hardware, chemicals, or processes were poorly suited for VC investment because they required significant capital, had long development timelines, were uncompetitive in commodity markets, and were unable to attract corporate acquirers,” the authors of “Venture Capital and Cleantech: The Wrong Model for Clean Energy Innovation” wrote in 2016.

After combing through the data, the researchers found that “the biggest money loser for VCs was the segment of cleantech companies commercializing fundamentally new materials and processes.” For example, solar companies that tried to replace silicon in solar panels ran into difficulties when trying to scale their model.

That said, other areas that also have capital-intensive models, like medical technology, didn’t fare nearly as badly. After comparing the two sectors, the researchers found that there were too few large companies willing to acquire clean tech start-ups. This unwillingness, coupled with the time and capital-restrictive nature of venture capital investing, created a challenging environment for clean tech companies.

More than 90% of clean tech companies funded between 2007 and 2011 failed to return even the initial capital to investors, the MIT Energy Initiative found. So it’s no surprise that while the need for greenhouse gas-reducing companies was recognized, for the most part, investors became weary of the space.

Clean Energy Ventures

Investors were beginning to dip their toes back into clean tech when, in 2017, Clean Energy Ventures decided to begin raising capital for its inaugural fund.

The new fund was spun out of Clean Energy Venture Group, a private investment vehicle through which the founders had been investing in green companies since 2005. Investments included companies like MyEnergy—which was acquired by Nest and then, in turn, by Alphabet—and Pika Energy, which was bought by Generac.

Dan Goldman, Temple Fennell and David Miller, the three co-founders of Clean Energy Ventures, had invested together before, but informally. That changed around 2016. They identified a need for funding clean tech companies just starting out — which the Street was largely unwilling to consider — and, given their deep ties to the clean energy entrepreneurship community, founding a new energy-specific fund seemed a logical next step.

They assembled a team comprised of people skilled both technically and operationally, and who had experience growing a company. Former U.S. Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz was among the people who joined the company’s strategic advisory board. Initially targeting a fund size of $75 million, the trio wound up raising $110 million.

From the get-go the fund’s strategy has been simple: instead of looking for start-ups that are trying to disrupt entire industries, focus instead on those that can improve existing companies.

“We’re constantly looking at where we can disrupt the value chain of existing incumbents,” said Fennell.

What that means is that the fund might invest, for example, in material companies whose products will help vehicles become lighter and therefore more carbon efficient, rather than in companies trying to fundamentally change the automotive industry.

Underlying every investment is an actionable plan for how that company can meaningfully contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gases.

“One of our criteria is we only invest in companies that we believe will reduce at least 2.5 gigatons of greenhouse gases or carbon equivalent tons between now and 2050,” Fennell said.

While the fund ultimately wound up exceeding its capital target, Fennell said that it was difficult to entice institutional investors back into clean tech. A good bit of their capital instead came from family offices, which typically have more flexible timelines and investing criteria.

Betting on clean tech

Clean Energy Ventures focuses on start-ups in the United States and Canada that are capital-efficient and scalable.

The fund plans to invest in around 25 companies over the next 4-5 years. The goal of every company in which Clean Energy Ventures invests will be, first and foremost, to drastically reduce emissions. But there should also be a clear path toward commercialization within 3-5 years. Given the accelerated time frame, Clean Energy Ventures typically looks for companies that can plug into “the existing infrastructure and the existing incumbent channels.”

The firm currently has seven companies in its portfolio, including SparkMeter, Leading Edge Crystal Technologies and LineVision.

SparkMeter, which has also received funding from Breakthrough Energy Ventures, led by Bill Gates, offers smart metering solutions for utility companies typically in remote locations. Leading Edge Crystal Technologies, which was spun out of Applied Materials, is developing cheaper, more efficient, and longer-lasting wafers for solar panels. And LineVision focuses on optimizing power grids’ reliability and safety, among other things, by using a network of sensors.

The fund has been known to invest alongside large, publicly traded companies like 3M, Emerson Electric and Applied Materials. Sometimes large companies will even bring startups whose technology they are interested in using to Clean Energy Ventures so that the fund can help them hone and scale their business.

Once the startup has gone through several funding rounds and proven that it has market traction and global scalability, Clean Energy Ventures will typically hand it off to larger partners.