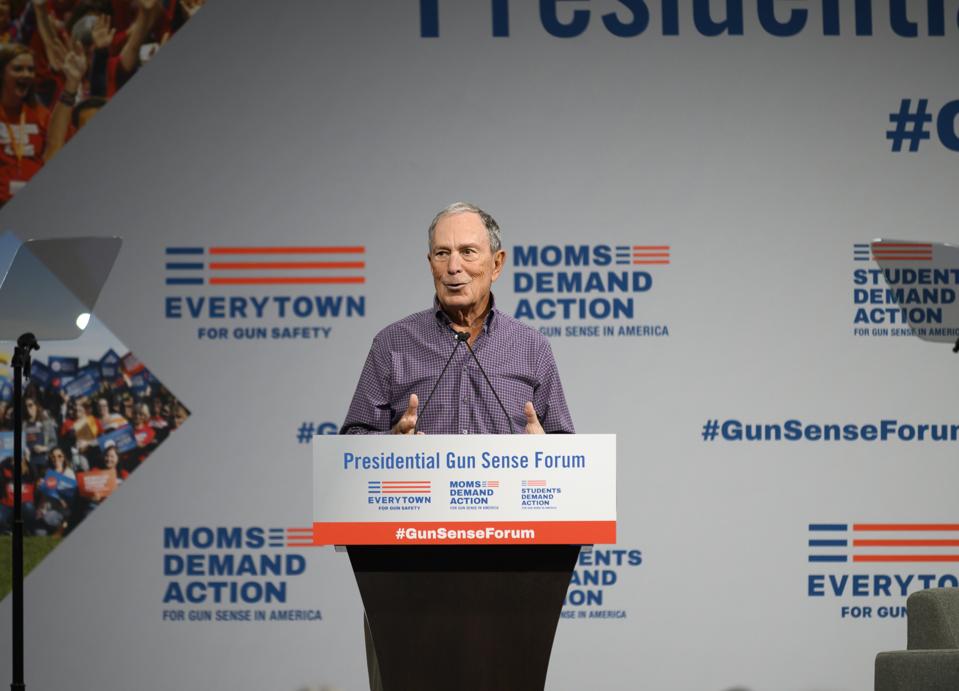

DES MOINES, IA – AUGUST 10: Former mayor of New York City, and Everytown for Gun Safety founder, … [+]

Whatever else they do, the wealth taxes proposed by senators and Democratic presidential hopefuls Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) will encourage the very rich to spend more of what they have and what they make. Some of that spending, such as contributions to charity, may benefit society. Some, such as buying US-made goods, may boost the domestic economy—at least in the short run. And some extra spending, by giving money to political candidates, would increase rather than reduce the political influence of the mega-rich, running exactly counter to the goal of some wealth tax advocates.

Sanders would begin taxing married couples’ wealth at $32 million and gradually increase the rate until they ’d pay an annual wealth levy of 8 percent on assets in excess of $10 billion. Warren would begin taxing wealth at $50 million, with assets in excess of $1 billion subject to a 3 percent annual tax.

An incentive to spend

Why would a wealth tax encourage the rich to spend? Think of it this way: If your assets above some level is subject to a stiff federal wealth tax, you’ll have a strong incentive to keep your wealth below that threshold. To put it another way, at the margin of a wealth tax, the tax encourages you to spend any additional amount you accumulate.

Economists have recognized a wealth tax’s perverse incentive to consume for a long time. I recently heard Harvard economist Greg Mankiw compare two hypotheticals to make the point, and the late Princeton economist David Bradford made the same argument years ago.

Imagine two very rich people. Joe is a spendthrift who buys yachts, fancy cars, diamonds, and other rapidly depreciating property. Because his spending habits keep his assets below the wealth tax threshold, he effectively is rewarded for his spending habits.

Jane makes the same annual income as Joe. But she is a saver and investor, prudently putting money away for the future or using her wealth to help create or expand businesses and job opportunities. Because she accumulates sufficient assets to be subject to the wealth tax, she effectively is penalized for saving and investing.

More charitable giving

The super-rich could stay under the tax threshold by increasing their charitable giving. And they could get a double tax benefit from their donations. They’d not only lower assets that would be subject to the wealth tax, but gifts to non-profits may also be deductible from taxable income subject to the income tax.

To be sure true charities benefit, the wealth levy would have to be carefully designed to prevent the wealthy from avoiding tax by shifting money to family foundations or other charities they tightly control. And while non-profits almost always can use extra money, large contributions often come with strings. And that is not necessarily healthy for charitable organizations.

More campaign contributions

But the more interesting issue is how a wealth tax would affect politics. Two leading advocates of the levy, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, argue that the super-rich have outsized influence in politics through their enormous campaign contributions. That thesis is itself debatable: One could argue that local car dealers and real estate developers (who tend to be rich but not super-rich) have more influence on a typical legislator than billionaires with a national agenda.

But there are exceptions. According to opensecrets.org, in 2018, Sheldon Adelson, his wife, and various related parties gave at least $123 million in campaign contributions (and perhaps more in “dark money” that cannot be tracked). Michael Bloomberg donated at least $95 million to campaigns, directly and indirectly. In that year, 13 super-wealthy people each gave $10 million or more to political candidates—nearly all to one political party or the other. And 80 others gave $2 million or more.

Some researchers conclude that while campaign giving by mega-donors has little direct effect on policies that effect their personal wealth, it does give the rich outsized influence in the general direction of government policy.

For the sake of discussion, then, let’s say Saez and Zucman are correct and it is both true and a bad thing for civil society that a few billionaires have excessive control over national politics. It is hard to see how a tax that will encourage more political contributions by mega-donors will fix that problem.

Increasing political donations is a way to offload wealth and avoid, or at least reduce, tax liability. And, of course, the super wealthy could use their newly-purchased influence to convince lawmakers to repeal the tax itself. We all may be better off if they just buy another yacht.