Family at fjord, Aure, More og Romsdal, Norway

Getty

What do I mean by “Goldilocks-level fertility rates”? Simply put, a stable, replacement-level (or thereabouts) fertility rate that ensures a sustainable balance between workers and retirees.

Earlier this week I wrote about the inexplicable decade-long drop in fertility rates in Finland. Back in August, I profiled Sweden, which has had swings in fertility rates at points when new family-benefit legislation motivated couples to have children earlier than otherwise.

To round out this little Nordic excursion, let’s look at Norway.

A little over a decade ago, in 2006, the BBC had this to say:

“Inger Sethov works for Norway’s second largest oil and gas company, Hydro. She is pregnant with her second baby. Five-year-old Lea will have a little brother or sister in June.

“For Inger and her partner Pierre, having children was never a difficult choice.

“’I’m entitled to 12 months off work with 80% pay, or 10 months with full pay. My husband is entitled to take almost all of that leave instead of me, and he must take at least four weeks out.’

“’Economic considerations never even crossed our minds when we decided to have children. It’s just not an issue. Of course that makes it easier for women to have more babies, it gives you an enormous freedom,” said Ms Sethov. . . .

“The paid leave is guaranteed by the National Insurance Act, and dates back to 1956. Because the leave is financed through taxes, employers don’t lose out financially when people take out their parental leave.

“The present system of 10 or 12 months leave with 100% or 80% pay was introduced in 1993. Since then, the fertility rate has been a steady 1.8 – higher than most European countries.”

So let’s take a look at Norway’s fertility rate.

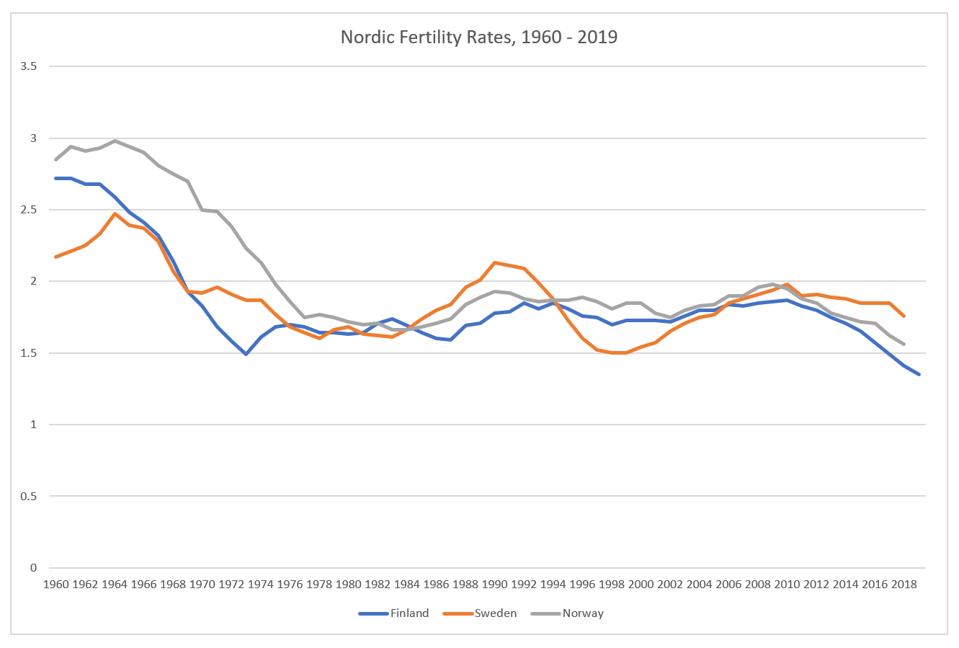

First, here’s Finland, Sweden, and Norway, since we looked at the first two in my prior article.

(Nit-picky comment: Sweden, Norway, and Denmark are the three Scandinavian countries. Finland is in fact not Scandinavian, but is included along with Iceland in a larger grouping of Nordic countries. Why am I not discussing Denmark? Because they’re not as interesting.)

Nordic fertility rates, 1960 – 2019

Own work

(Data for years prior to 2017 is taken from the World Bank database; for the most recent years, see my prior Finland and Sweden articles as well as 2018 and 2019 reporting on prior year’s Norwegian rates.)

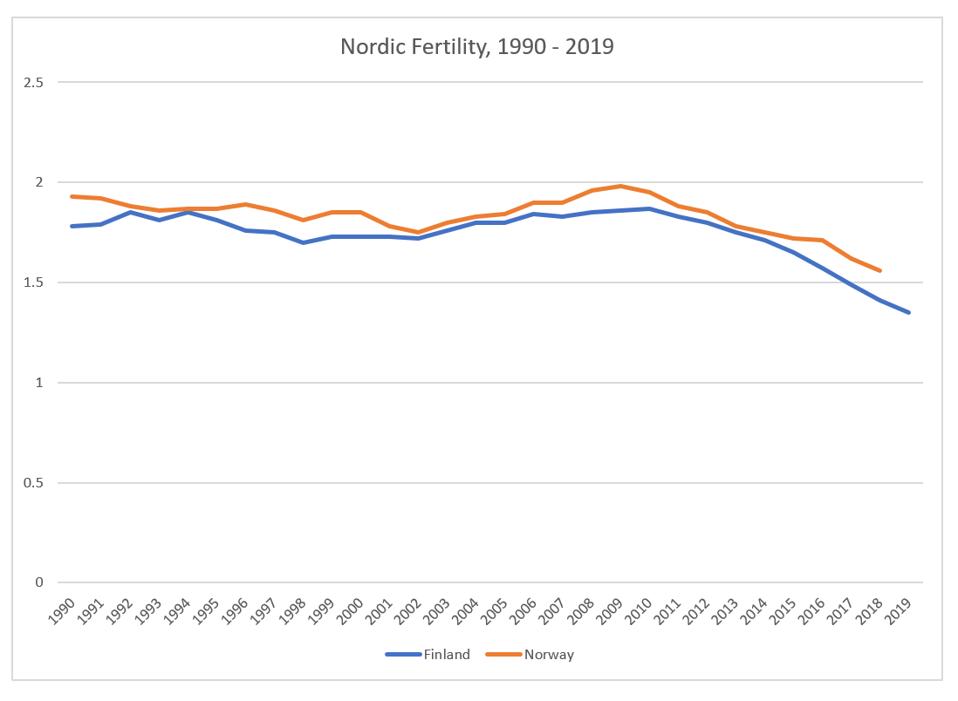

Looking at recent years, and excluding Sweden (pay attention, the colors shift!), we have:

Nordic fertility rates, 1990 – 2019

own work

What’s noteworthy here?

First, something missing: the boost to parental leave benefits in 1993 appears to have had no effect on fertility rates.

Second, after an early-2000s small drop-off, rates rose considerably, from 1.75 to 1.98 between 2002 and 2008.

What happened in 2002? Of note, the child benefit system, cash payments to parents of all children under 18, was established (or significantly modified) in 2002. Did this boost enthusiasm for childbearing?

In any event, the fertility rate peaked in 2008. Not only has it been on the decline since then, but the 2018 rate of 1.56 is the lowest Norwegian fertility has ever been.

What’s going on? The Norwegian site News In English reports no consensus explanation, only citing speculation that women are increasingly spending more years in school. This seems an unlikely explanation for such a dramatic drop in a single decade. In the United States, the tumbling birth rate has been blamed on poor economic conditions, but Norway’s oil wealth continues to bring it prosperity, as evidenced by its exceptionally low unemployment rate.

An analysis of the fertility rates by immigration status suggests a promising clue: rates for immigrant women, while higher than for native-born Norwegians, have been dropping considerably: from 2.29 in 2010 down to 1.87 in 2018. This works as an explanation in the U.S., with respect to Hispanic women. But there are so few immigrants in Norway that this only brings the fertility rate up by a level of 0.07, not enough of an effect for that group’s decline to drive the larger decline.

Here’s an insight from an article in Science Norway (reprinted from KILDEN Information and News About Gender Research in Norway): according to researcher Eirin Pedersen at the University of Oslo, the generous welfare state and the norm that women work and place their children in childcare centers is only part of the explanation for Norway’s (at the time, comparatively-higher-than-elsewhere) birth rate); she says,

“The welfare state has an impact on our culture. A German colleague pointed out the following to me: in Scandinavia, it is hard to imagine the possibility of living The Good Life without children. This is not necessarily the case in the rest of Europe.”

And, given that the pattern is the same for Norway and Finland, let’s pull Finland back in, via a 2018 article by demographer Lyman Stone, “Feminism as the New Natalism: Can Progressive Policies Halt Falling Fertility?” Citing available research, he reports that paid leave programs, no matter how generous, have only scant effect on fertility rates. What he notes is that the cultural value that “The Good Life involves having children” has changed;

“Desired fertility has plummeted in Finland, and the limited data for Sweden suggests a similar trend may be ongoing. . . . This helps explain what’s happening. In Finland and perhaps also Sweden, fertility is falling because, since the recession, something is changing with cultural values for Finns and Swedes: women simply want fewer kids. This isn’t a long-running Nordic trait, but something fairly new.”

(The Finnish data showing a drop in ideal fertility from 2.6 in 2006 or so to 2.1 in 2015, is based on a study specific to Finland; the Eurobarometer study collects data about all of Europe but was last conducted in 2011.)

Of course, that leaves unanswered the question: why would Nordic culture have changed in the past decade? And what does that say about cultural preferences for children more broadly speaking?