A man enter the doors of the ‘WeWork’ co-operative co-working space in Washington, DC.

Mandel Ngan | AFP | Getty Images

WeWork has become a cautionary tale for private equity and venture capital executives who are learning that growth at all costs doesn’t always cut it in public markets.

The real estate start-up has seen a number of set-backs in recent weeks, including a dramatic cut in its valuation and its biggest outside investor, SoftBank, urging the company to shelve the offering.

Mark Goldberg, partner at Index Ventures, said those events are changing conversations about what it means to be IPO-ready and the “pendulum is swinging back to a focus on cash flow instead of growth at all costs.”

“The concerns around WeWork’s valuation are a splash of cold water in the face of many private-company CEOs and CFOs in Silicon Valley — especially those with capital-intensive models,” said Goldberg said. “It’s shaking up the conversation in board rooms around what metrics a company should prioritize.”

Sources told CNBC’s David Faber earlier this week that the valuation target for the real estate company was being cut by roughly $20 billion because of weak demand. The company had been valued at $47 billion after its last private funding round. But it’s still heading towards an IPO. On Friday, Faber was hearing the valuation could be $15 billion or lower.

On Friday, the We Company, owner of WeWork announced plans to list on the Nasdaq. It is also changing corporate governance to lessen CEO and founder Adam Neumann’s voting power.

WeWork revealed a $900 million loss for the first six months of 2019 on revenues of $1.54 billion in its filing to go public. But it’s hardly the only company to head for public markets with huge losses. Uber went public in May after staying private for a decade, funded by venture capital bets from SoftBank, Google, and the Saudi Arabian government. The ride-hailing company lost $5.2 billion in the second quarter. Uber’s rival Lyft, posted a 2018 loss of $900 million ahead of its March IPO.

Management teams may start steering companies towards profitability sooner, Goldberg added.

“In the case of WeWork, they are learning that the North Star they’ve been following for years may have been misleading,” he said. “The public markets are sending a strong message that profitability matters.”

Many companies have had relatively easy access to funding despite the monster losses. “It was all about growth at all costs; now it’s about sustainable growth,” Goldberg said.

Jihan Bowes-Little, managing partner and co-founder of Bracket Capital, said certain aspects of WeWork’s struggles don’t apply to every money-losing peer. Still, he said private market investors are rethinking steep losses more broadly, and turning towards companies that “combine high-growth rates with a focus on strong unit economics.”

“I do think the weak demand for the IPO is significant, particularly with respect to the extent to which both public, and private, market investors are focusing on strong unit economics in addition to user/customer growth,” he said.

IPO dreams meet reality

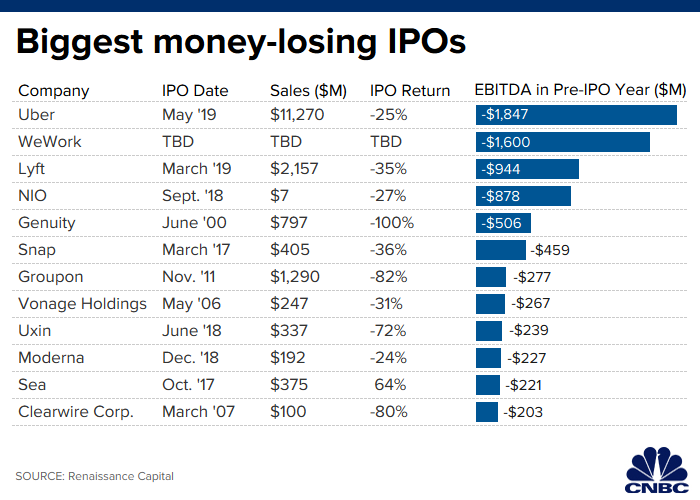

Public market investors have been burned by some money-losing IPOs in the past two decades.

Renaissance Capital looked at the companies with the biggest losses over the past two decades in the 12 months ahead of their IPO. Uber had the deepest losses of any company ahead of its IPO, according to the data, followed by WeWork in second place. All but one, a company called Sea, which shifted its strategy from a payments company to a live gaming platform, is under water. Uber is down 25% from its IPO price, while Lyft has dropped 35%.

“It’s a cautionary tale — large, money-losing IPOs tend to be problematic for investors,” said Kathleen Smith, Principal at Renaissance Capital, a provider of institutional research and IPO ETFs. “Investors should be really cautious about how easy it is to how dangerous these stocks can be in the public market.”

Smith said one reason is robust private markets, where investors are willing to incubate companies for years, “without them having to show they can earn money.” WeWork was a healthy signal for the IPO market, and a sign that markets may avoid getting “overheated.”

Columbia Business School professor Len Sherman and former senior partner at Accenture, said while he doesn’t want any particular start-up to fail, WeWork’s troubles could be a necessary check on venture capital valuations.

“SoftBank in particular has done a pretty grave disservice to the whole private capital marketplace and valuations,” he said. “WeWork will have a chilling effect on some of these private equity companies thinking they can just keep pumping valuations up artificially, and still walk away with a bundle of money.”

Low demand for WeWork could be proof that the IPO market is still the most “effective arbiter around,” according to Sherman.

“I hope this brings us back in a more rational direction,” he said.

Others see the issue as more unique to WeWork, not a signal of impending change in private markets.

Sheel Mohnot, a partner at early-stage venture capital firm 500 Startups, said the lack of enthusiasm from some investors shows what the true appetite is for the company but it won’t have strong trickle down effects.

“I don’t think there are many broader implications — many of us looked at WeWork and said it wasn’t working,” he said. “There’s something wrong with that company, not the overall market.”